The United Methodist Church is in the middle of a theological crisis. Some will call this a crisis regarding human sexuality, others will say the crisis centers on justice or biblical authority or Christian orthodoxy.

Many have gone to John Wesley for help in resolving these crises, as we would expect. But I wonder if we could use some outside help in this instance. I’ll suggest here that Martin Luther may offer a different view of our impasse.

Simul justus et peccator

One of Luther’s most famous phrases is simul justus et peccator. With it, Luther claimed that a Christian is at once both righteous and a sinner. We are sinners, and we are saints. For the one who imagines himself only a saint, Luther’s claim instills humility. For the one who imagines himself only a sinner, Luther’s claim offers hope.

We hear a similar notion in Solzhenitsyn’s most famous quote:

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.” [note]From The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956[/note]

Luther and Solzhenitsyn remind us that evil is not simply something out there. Look inside each of us and we will find it.

Luther emphasized this well in another of his famous phrases: “Sin boldly!”

What can he mean by “sin boldly”? Shall we go on sinning so that grace may increase? By no means![note]This is from Romans 6:1-2[/note] To understand, we should look at the context for that exhortation –– a letter to his friend Philip Melanchthon:

“If you are a preacher of mercy, do not preach an imaginary but the true mercy. If the mercy is true, you must therefore bear the true, not an imaginary sin. God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners. Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong [i.e. sin boldly], but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world […] Do you think such an exalted Lamb paid merely a small price with a meager sacrifice for our sins? Pray hard for you are quite a sinner.”[note]emphasis mine[/note]

Luther’s “sin boldly” makes more sense to me when I see it in this context. This isn’t to encourage a friend into sin––”Go do what you please! God will forgive you.” This is to make Luther’s friend acknowledge his true state as a sinner. Don’t treat your sinfulness as imaginary, as something insignificant, as a few minor mistakes. You’ve heard those kinds of “confessions”––”I’m sure I’ve done some things wrong”; “Mistakes were made”; “I’m only human.” Instead, “sin boldly” tells us to recognize our true nature: “You are quite a sinner!”

The one who lets his sins be strong (i.e. sins boldly) is the one who can cry out with the Apostle Paul, “What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death?” [note]Romans 7:24[/note] He is also the one who can then join Paul in the exclamation, “Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!” [note]Romans 7:25[/note]

Luther calls every Christian to humility––to recognize our own sinfulness.

And Luther calls every Christian to wonder and gratitude––to recognize God’s undeserved gift of life and salvation through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Humility in conflict

How rarely we “sin boldly” in the church today! It seems we recognize others’ sinfulness quite easily but consider our sins much less significant––much closer to the imaginary variety. Michael Gerson named a similar phenomenon in American politics.

This is unsurprising in American politics. It should not be the norm for the Church.

Would a view of ourselves as simul justus et peccator give us the humility to engage each other with less hostility and more grace? Would Solzhenitsyn’s distinction about the line dividing good and evil slow us from tossing pejorative grenades across our supposed lines of division?

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds,” Solzhenitsyn writes. But we have found those evil people! We accuse the other side of racism, bigotry, white nationalism, homophobia, fundamentalism, heartlessness, and injustice. Or we claim based on one issue that an entire group must have no interest in holiness, biblical authority, or following Jesus. These false lines we draw see only justus in ourselves, only peccator in the other.

I wonder if Luther’s simul justus et peccator might give us the humility to handle these conflicts differently. Might it prompt more repentance and less accusation? Might it prompt us to deal gently with those going astray, since we know ourselves to be sinners, too?

The church as simul justus et peccator

When Luther spoke of us as simul justus et peccator, he spoke of us as individual Christians. In each of our bodies, we are at once sinner and saint. I want to suggest that simul justus et peccator may have a broader application––not only to our bodies, but to our Body.

Is it fitting to say that the Church, the very Body of Christ, is at once a sinful and a holy Body? Is it right that we should call this Body “quite a sinner”?

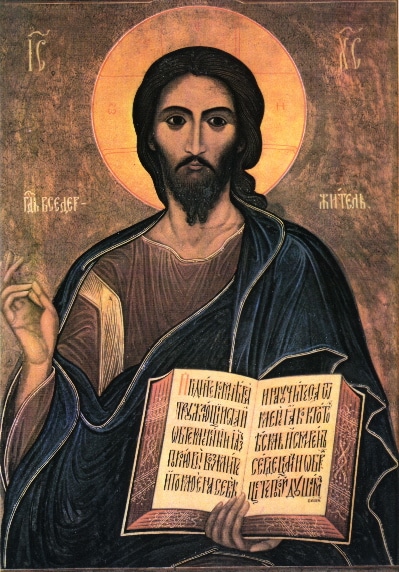

This does not seem fitting of the true Church––the one that is truly Christ’s Body. Because in Christ is no sin. And no one who lives in him keeps on sinning.[note]1 John 3:5-6[/note] I believe this. It’s the great doctrine of Wesleyan holiness, which has transformed my life. In the true Church, the true Body of Christ, there is no sin.

Wesley describes it this way:

“If the Church, as to the very essence of it, is a body of believers, no man that is not a Christian believer can be a member of it. If this whole body be animated by one spirit, and endued with one faith, and one hope of their calling; then he who has not that spirit, and faith, and hope, is no member of this body. It follows, that not only no common swearer, no Sabbath-breaker, no drunkard, no whoremonger, no thief, no liar, none that lives in any outward sin, but none that is under the power of anger or pride, no lover of the world, in a word, none that is dead to God, can be a member of his Church.” [note]In Sermon 74, “Of the Church” [/note]

With Wesley I affirm that Christ’s invisible Church is holy, pure, and set apart from sinners.[note]Hebrews 7:26[/note] We are these because Christ is these and we are his Body.

But are any of our visible churches without thieves or liars? Are any without people under the power of anger or pride? No! The church remains full of sinners. As a Body, we are full of sin. So we confess each week, “We have failed to be an obedient church.”

The church, in all of its visible forms, is simul justus et peccator.

And the line dividing good and evil does not cut between one faction and another, between one congregation and another. It cuts through the heart of every body that calls itself church.

Orthodoxy

We need to make an important distinction about orthodoxy before we carry the analogy from Luther too far. When Luther spoke of people as simul justus et peccator, he was not referring to all people. This was a designation for confessing Christians.[note]I’m indebted to Dr. Steve O’Malley for this point.[/note] They had been baptized into the Church under the Apostles’ Creed as the common confession of faith. They confessed God as Father, Christ as Lord, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting. The sinners Luther referred to were made righteous by living by this faith. Righteousness is not our own, it comes only by faith.

I want to suggest that the visible church is a Body both sinful and righteous. But it is only righteous by faith in Christ. A church that does not confess and mean the historic creeds of the Church as the historic Church confessed and meant them is no church at all. At least, it is not a Christian church. All faith outside of these affirmations is, by definition, heterodox––or heresy. If this sounds like an exclusionary statement, that’s because it is. All real things have bounds,[note]I originally had “All things but God have bounds,” but even an omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent God has definition. God is everywhere, but God is not everything, and everything is not God. (i.e. We are not pantheists.)[/note] and the bounds of Christian orthodoxy were constituted long ago in these universal confessions.

There are some who call themselves United Methodists who reject the Christian faith articulated by the Church’s early ecumenical councils. We have some among us[note]Please do not confuse my “some” to suggest that all, or even most, of any particular faction fit these descriptions[/note] who scoff at the notion of Christ’s real, historical, bodily resurrection, some who believe the Bible is a mere human work with no ultimate authority, and some who honestly have no interest in following the way of Jesus if it should lead them somewhere different than where they would like to go. What I’ve written above is not about those people. They are not those whom Luther referred to as simul justus et peccator. A Body that does not confess the Christ of faith is not the Body of Christ.

Debates about orthodoxy have become common in our current crisis. Should we extend it beyond our definition above? Some have called the “traditional” position on human sexuality the orthodox position. I reject that here. I think orthodoxy is best left to refer to conciliar orthodoxy. James K. A. Smith articulates this well: “The word [orthodox] is reserved to define and delineate those affirmations that are at the very heart of Christian faith—and God knows they are scandalous enough in a secular age. Perhaps we need to introduce another adjective––’traditional’––to describe these historic views and positions on matters of morality. ” [note]From this blog post, which is worth reading in full.[/note]

What do we do with a sinful Church?

And so we have a body––the very Body of Christ––at once righteous and sinful. We’re uncomfortable with the church as simul justus et peccator. And we should be. God has set in our hearts a different image of the Church––as a bride making herself ready for the wedding of the Lamb,[note]Revelation 19:7[/note] preparing as one to be beautifully dressed for her husband.[note]Revelation 21:2[/note]

Our disagreements about what we call sin are presenting themselves as a theological crisis in our church. Underneath them is another tension: What do we do with a sinful Church?

Who will rescue us from this body that is subject to death?

This post attempts to establish some foundations. In a post to follow, I’ll focus on another aspect of Luther’s theology––the theology of the cross––along with implications for the United Methodist Church and for those who might consider leaving.

Like it? Or just want to discuss it more? I’d be honored if you’d share it. Click here to share on Facebook. Click here to share on Twitter.