In an earlier post, I suggested that the pro-life cause may have been the most galvanizing political issue since slavery for American evangelicals.

A note: I’m neither endorsing this as clearly appropriate (many other issues are serious and could have been galvanizing––especially regarding civil rights), nor would I call it inappropriate (the numbers are tragic). I’m simply naming that this has been a galvanizing issue, whether you agree that it should have been or not.

For evangelicalism as a whole, I’d like to suggest that religious affiliation led the way to political affiliation. But somewhere along the way, I wonder if the political cart got ahead of the religious horse.

How evangelicals became Republicans

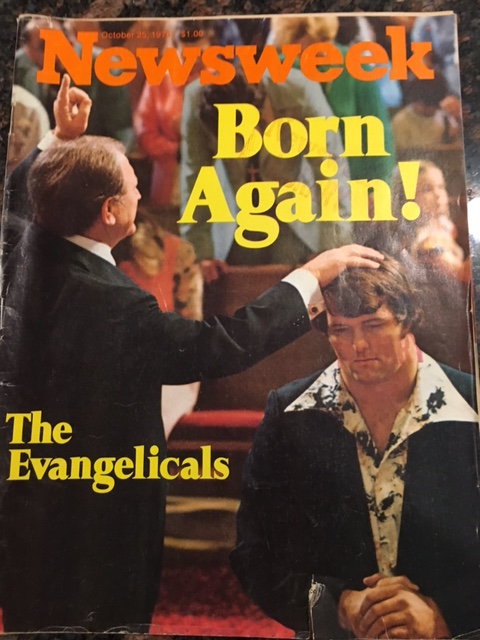

In 1976, Democrat Jimmy Carter became the first “born again” evangelical to become president. Newsweek declared it “The Year of the Evangelical.”

To be sure you caught that… The first “born again” evangelical to be elected President of the United States… was a Democrat. Less than a half-century ago, evangelical did not mean Republican. In fact, the election of a Democrat[note]this particular Democrat––not that all evangelicals were Democrats[/note] to the presidency spurred Newsweek to deem it “The Year of the Evangelical.”

And then in 1980, the Republican Party added anti-abortion planks to its platform. They have continued as the anti-abortion / pro-life party to this day.

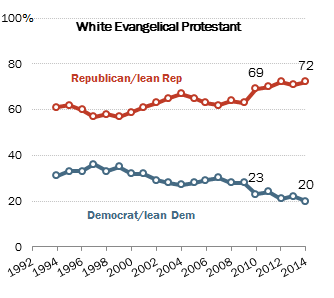

By 1992, white evangelicals leaning Republican outnumbered Democrats 2 to 1. By 2014, white evangelicals leaning Republican outnumbered Democrats 7 to 2.

In April 2018, a Public Religion Research Institute survey showed white evangelical support for President Trump at an all-time high: 75% compared to general population favorability of 42%.

For many people, evangelical and Republican have become one and the same.

It was not this way in 1976 when Jimmy Carter was the first evangelical elected to the presidency. But as anti-abortion / pro-life policy made the Republican platform, evangelicals flocked to, and took up leadership in, the GOP.

The dangers of good activism

If we think we may be among those who would have flocked to the Liberty Party in the 1800s because of its anti-slavery platform (see that earlier post), I don’t think we can blame evangelicals for doing the same because of the GOP’s anti-abortion platform.[note]To be sure, there are other ways to advocate for the lives of unborn children. Especially by offering hospitality and the option to adopt to pregnant women unprepared for a baby. I’ve watched several pro-life advocates (some whom I’m related to) make serious personal sacrifices to do exactly this. And they have also advocated for changes in public policy. The two don’t have to go together, but they’re not mutually exclusive, either.[/note]

But over time, that good activism has led many evangelicals to be more Republican than evangelical. This large voting bloc came to the political party primarily because of one issue. They saw anyone who was anti-abortion as ally and all others as foes.

An interesting thing tends to happen over time with allies and foes. Our allies begin to look like heroes to us. We’re so committed to them on the one issue that we begin to see all of their battles as ours. And our foes begin to look like villains to us. We’re so opposed to them on the one issue that we begin to see every battle as a battle against them.

So today white evangelicals are the demographic group most likely to support refugee bans and deportation of immigrants living in the U.S. illegally.[note]Yes, I know even the terminology for this group of people has become a political debate. Here I use the terminology used by pollsters in the linked poll.[/note] They have more positive views toward guns than the general public. And they’re the group least concerned about environmental protection. All of these stances have some kind of reasonable case associated with them (some of them, in my humble opinion, a very weak case). But the case for each is mainly a Republican case. We can’t argue that Christian faith obviously leads us to any of these stances. In fact, on the surface at least, Christian faith would lead us in the opposite directions.

It is not because of biblical arguments that white evangelicals have become the single demographic group most likely to say the U.S. has no responsibility to accept refugees. Not when the Bible persistently advocates for special care for the foreigner, the fatherless, and the widow. (See Deuteronomy 10:18; 14:29; 16:11, 14; 24:17, 19-21; 26:12-13; 27:19; Psalm 94:6; 146:9; Jeremiah 7:6; 22:3; Ezekiel 22:7; Zechariah 7:10; Malachi 3:5)[note]One well-meaning evangelical recently asked, “But are there any examples in the Bible of a group of foreigners who are growing in numbers and could take over the country?” He wasn’t encouraged when the only example I could think of came from Exodus 1: ” ‘Look,’ [Pharaoh] said to his people, ‘the Israelites have become far too numerous for us. Come, we must deal shrewdly with them or they will become even more numerous and, if war breaks out, will join our enemies, fight against us and leave the country.’ So they put slave masters over them to oppress them with forced labor.”[/note]

I expect this century’s general evangelical disregard, or even hostility, toward those who are not American citizens to look as bad for the Christian cause in the future as the American church’s failure in the last century to speak and act with one voice against lynching and segregation.

Religion led many evangelicals to the Republican Party over the last fifty years because of abortion policy and its wider attitudes toward abortion (as something to lament rather than openly celebrate). But once they got there, the political cart of the full Republican platform got ahead of the religious horse that brought many evangelicals here. White evangelicals, as a voting bloc, seem now more inclined to support and oppose issues based on partisan divides than based on an examination of Scripture and the Christian tradition.

The threat of religious idolatry

Is it possible that political partisanship is one of today’s most threatening idols? Someone’s political party identification is now far more reliable than their religious identification for predicting their stance on issues as wide-ranging as abortion, the environment, or immigration. Their political party identification seems more reliable than their faith for determining when a politician’s misdeeds are cause for moral outrage and when they’re an occasion for understanding and forgiveness.

This is not only a problem among white evangelical Republicans, but also among many Christian Democrats who insist their faith has led them to their political stances. When one politician talks with messianic overtones, the partisan Christian responds, “We already have a savior!” Yet when they hear similar statements from their own preferred party, they respond with silence or celebration.

Christians of all stripes, it SHOULD NOT BE THIS WAY! This is not far from idolatry, if it isn’t idolatry, properly defined. Neither of America’s political parties derives its standards from the Christian faith. Both parties include people of virtue and both include people whose behaviors should be cause for moral outrage. If we find ourselves always morally outraged by one side’s policies or people and always defending the other, it may be a signal that our politics have become our gods.

It may have begun with good activism. It’s threatening to become idolatry.

Agree? Strongly disagree and want to discuss it more? “I don’t agree with all of this, but it raises some interesting points…”? Share it using the social media links here. Or send me an email for follow-up discussion. Or if you haven’t already, click here to subscribe for more. Thank you!