Only God is infinite. The rest of us deal in finite resources.

The money available to us is finite. The time available to us, at least on this old earth, is finite. Will we use them well, or will we squander them?

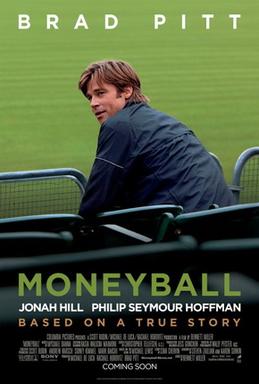

I referenced Moneyball in the previous post. In the based-on-a-true-story book and movie, the Oakland A’s are using a limited budget and trying to compete with the Yankees. (Only God is infinite. But the Yankees’ resources seem close.)

How does a team like the A’s with a $41 million payroll beat the Yankees with their $125+ million payroll? They figure out how to maximize their resources. While most baseball teams are relying on “medieval” thinking––doing it because they think it should work, because it’s the way they’ve always done it, etc.––the A’s rigorously study what makes a difference and follow the results to new ways of operating, unusual or uncomfortable as they sometimes are.

Maximizing the church’s resources

In the coming years, the church must find ways to maximize its resources. This is especially important because our battle is especially important. Our competition isn’t the Yankees. Contrary to popular belief, our competition isn’t the mega-church down the street, the Baptists, the Roman Catholics, etc. Our competition is sin, injustice, and heresy.

These are relentless opponents. But our infinite God has given us all that we need for the battle. Now the question: Will we steward it well, or will we squander it?

In the previous post, I wrote about a group that spent $15 million on church planting over the last decade with almost nothing to show for it today. That was a tragic loss of resources. I’m not quite ready to call it squandering. Perhaps that group was neither reckless nor foolish. Perhaps they were careful, thoughtful… and unlucky. Perhaps they were just doing the best they could. They didn’t know any better They provided, if nothing else, a very expensive set of experiments in church planting.

What would be reckless and foolish is if we didn’t learn enough from that expensive set of experiments before running off to try more.

I want to suggest here that the United Methodist Church is an excellent experimental lab. With the level of autonomy each Annual Conference and local church has, we’re simultaneously running thousands of experiments. We have enough history that it’s time to study those experiments more closely and let the results guide us. If we don’t do that, we’re liable to squander our resources––usually out of a desire to keep doing things the way we want to do them.

Three areas where the results should challenge what we’re doing

Tenure and Transition

In an earlier post, I shared several studies related to pastoral tenure and transition. These studies showed what every study I’ve seen shows: churches do much better with long pastoral tenures and few pastoral transitions.[note]Some people may suggest the causal relationship actually runs the other way. Though there must be at least some truth to this, our study showed how even successful long-term pastorates suffered losses in their early years.[/note] When I sent results of one of these studies to a friend, he asked, “Do we even need to keep running more studies?” We know by now. My plea to leaders across the UMC: do what you can to increase pastoral tenures and reduce transitions.

While many said it sounded like a good idea, there were also several who corrected me about our problem. The problem wasn’t too many transitions. The problem was that “we don’t do transitions well.”

Do you see what that suggestion affords? A chance to keep making moves as often as we want to, but with more conversation along the way about how to do it “well.”

The problem: We have nothing more than anecdotes about how to do transition “well.” We do, however, have clear evidence that we should try to create fewer occasions of pastoral transition. One retired United Methodist Bishop cited this as the single biggest problem in our denomination. “We have to get our heads out of the sand,” he said. I thought he must have switched topics to our bigger denominational controversies. “No,” he said, “about pastoral transitions.”

We shouldn’t be too surprised that the frequent shuffling of pastors is harmful to ministry. The practice works against basic biology. Harvard professor Robert Putnam writes, “[F]or people as for plants, frequent repotting disrupts root systems. It takes time for a mobile individual to put down new roots […] frequent movers have weaker community ties.”[note]In Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 205.[/note] That makes frequent moving harmful for pastors and for churches trying to minister to their communities.

I went to a cooking class a few years ago where the chef talked to us about how amateur cooks feel a need to constantly move the meat around on the grill top. He talked about all the reasons that was unnecessary and could be harmful to the final product. “For some reason, you feel the need to keep moving that meat around. Maybe you need to feel like you’re doing something. You have to stop! Put it there, and then LEAVE IT THE HELL ALONE!” Though I’m not sure that’s quite the way we’d say it to Bishops and Cabinets around the denomination, the chef’s admonition seems fitting, in principle.

We have enough evidence to make this change. Can a pastoral transition be beneficial to a church? Of course! But it will be the rare exception to the rule.[note]In our study, 70% of churches declined after a transition, including 90% of churches that had previously experienced 10% growth or more.[/note] If a Conference’s median pastoral tenure is falling, rather than rising, we have reason to ask whether they’re squandering one of their most important resources. A change to lengthen pastoral tenures––I’ve suggested a target average of 10 years––would involve a change to many standard practices and cultural norms. It wouldn’t be easy. But it’s needed. I’ve provided some practical suggestions about how we could do this in the recommendations section of the bigger research study.

I’ll share pt. II next week. It’s on church planting and includes some research that may confirm or contradict how you think church planting works. JOIN my e-mail update list to be sure you see it.