I’m now in my 20th year of pastoral ministry. During my earliest years of youth ministry, I remember another pastor advising, “Only do this if you can’t do anything else.”

The implication was that ministry work is hard, that other routes would likely be more rewarding if they were options. “Only do it if you know you’re called. Otherwise you’ll never make it.”

I didn’t know I was called. Not for a long time.

I’m still not sure I’m called in any permanent sense, as if it’s pastoral ministry or bust for the rest of life.

Calling is a strange thing. At least in a lot of the ways we treat it today––as a personal certainty about our life’s work. Frankly, I think we give it too much attention in ministry world. We expect ministry candidates to articulate with clarity how they know they’re called to ministry. This usually carries the suggestion that this is the only proper path for their lives. To do anything else would be running from God’s will for their lives. There’s a popular testimony that goes that way: “I knew I was called ten years ago. But I spent the first five years running from it…”

Here’s an example of how I hear us commonly talk about calling:

I understand some of the bad reasons that linked article is trying to avoid, but the tweet paints a common, one-sided picture of calling and ministry. In church world, we spend a lot of time talking about (1) personal sense of calling, and (2) how hard ministry can be. Twenty years in, I’d like to offer an alternative perspective on calling and ministry.

1 – Another perspective on calling

How I ended up in ministry

I only even considered pastoral ministry because of Jerry Ernst. He asked me to lead our youth group during my last two years of high school, asked me to preach on youth Sunday during both of those years, and asked me to serve as the interim youth minister for the summer after he moved away. All of these came as surprises. Jerry entrusted me with much more than I imagined I could or would be entrusted with.

I considered it because Aaron Mansfield came to me after I preached for the first time and said, “If you do anything other than this with your life, you’re going in the wrong direction.” (I took it as kind encouragement. He has apologized several times since for coming on a bit strong.)

I started into pastoral ministry because Steve Drury at Trinity Hill UMC asked me to serve as an interim youth minister for a summer while I was in college. When I thought I’d finish out the summer and move on, he and a group of parents asked me to stay. That interim turned into three years.

I stayed in pastoral ministry because when I told Paul Brunstetter it was time for me to move on from youth ministry, he rearranged staffing structures and told me I could leave youth ministry but shouldn’t leave ministry altogether.

I stayed in pastoral ministry because Dulaney Wood heard I was making plans to move on, asked me to come to his house, and told me I was making the wrong decision.

I came back to pastoral ministry after a year overseas because after I had told Mike Powers I was moving on to something different, he came back to say, “Are you sure?” So I re-considered … and told him a second time I was going to move on. And he came back yet again.

Those are moments. A few people have supported and encouraged me beyond what any moment would adequately capture––Todd Nelson, Jonathan Powers, Chad Foster, my parents, and my wife. Early on, Emily said she’d do whatever it would require of her for me to do this––work less, work more, rearrange her schedule, recalibrate her expectations––and she has.

It’s difficult to stop once I begin naming names. There are so many others whom I should list. That long list represents a church that has consistently affirmed my role in ministry with their words and actions.

I worry that all of the above could come off as some kind of humble brag—if there were any feigned humility at all. And that would be the case if those people were affirming talent. But I don’t think that’s what was happening. Frankly, if people were judging by particular aptitudes, I may have had some people encourage me in different directions. Pastoral care didn’t come naturally to me. Preaching often was too academic to connect well with people. I was awful at remembering names. But I think these people had a sense about what God was doing—sometimes a sense enough to see past my inadequacies—and they were able to speak from that when they told me I was in the right place.

This is all very personal to me, but it’s also a reflection on what I believe is a healthier way of understanding calling. We get a few instances of miraculous calling stories in the Bible––Moses at the burning bush, young Samuel in the Temple, Saul/Paul on the Damascus road. But these are exceptions. The book of Acts gives us the more typical pattern:

Paul and Barnabas appointed elders for them in each church and, with prayer and fasting, committed them to the Lord, in whom they had put their trust.

Acts 14:23

Perhaps for a few people called to daunting tasks, a miraculous sort of calling is necessary––that kind of thing that leaves someone with an “unshakable call from God.” But for most of us, I expect the primary sense of calling will come from community. Others in the church community recognize that you should be leading and entrust you to lead. At the least, calling will need to be confirmed by community. The Israelites still had to choose to follow Moses. The people had to listen to Samuel. The apostles and elders of the early church had to confirm Paul’s calling.

(Some of the prophets seem to be exceptions. They followed God’s calling despite almost no positive reception from the people. But the calling to prophetic ministry is not the calling to pastoral ministry.)

I haven’t made it through hard times primarily because of a personal sense of calling. I’ve made it through them because of a community of people who continued to reaffirm that I should be there, even when I was less sure myself.

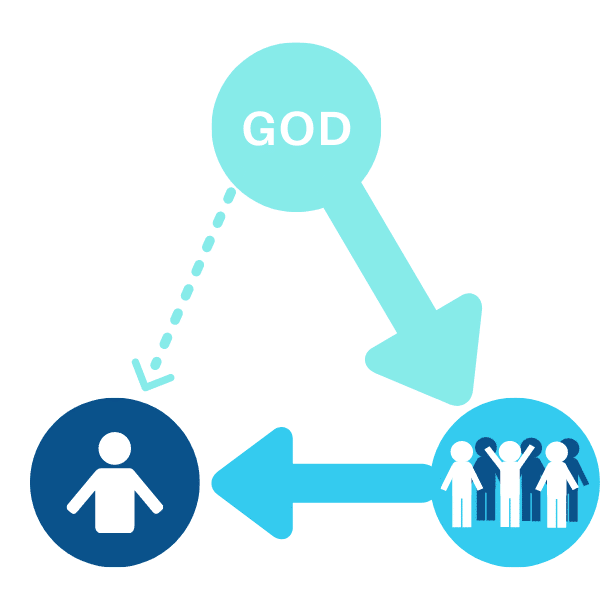

This is not to replace the role of God with the role of the church. It’s to identify how God was at work throughout. And at times, that came through other divine confirmations––an assurance from Scripture or in prayer, an unexpected occurrence at just the right time. But the primary way that I’ve experienced God’s calling has been mediated through the community around me––a community that I believe is better equipped to listen to God and interpret his will than I am on my own.

The Christian community’s role in calling

We tend to talk about and view calling like this:

But my experience has been closer to this:

This is actually closer to the historical pattern of calling to ministry. That inner, personal sense of calling is a rather new focus in the life of the church. Francis Dewar describes the more typical pattern in history:

Questions probing the candidate’s inner sense of calling do not appear in church ordinals before the sixteenth century.

…

[I]n the first ten centuries of the Church’s history, it was the local Christian community that had the chief part to play in the choice of its leader. In fact, the Council of Chalcedon in 451 forbade ‘absolute’ ordinations.

…

You could not be ordained unless you had been asked by a particular Christian community to be its leader. Conversely, if you ceased to be the president of your community, you automatically became a layman again.

Called or Collared? by Francis Dewar, pp. 9-10

This has enormous implications. I’ve seen some people go to seminary, devote years of their lives, and accrue up to 6-figure debts to receive an M. Div. degree only to learn that no church would entrust them with leadership. They had a personal sense of calling, but it wasn’t one that had been confirmed and promoted by the church.

In my dream world, seminarians wouldn’t pay for seminary. Seminaries wouldn’t allow you to pay (or even worse, take on debt) to receive an M. Div. degree. You could only go if you had a sponsor. Is there a church, a denomination, a Christian organization that believes in you enough to foot the bill? (To be sure I’m not over-speaking here, I don’t mean to suggest to you that if you’re currently in seminary and paying for it yourself, that you must not be called to ministry. Our systems aren’t currently designed to function according to this model. But I wish they were.)

A note to Christian communities: We have a crucial responsibility to listen to God on behalf of others, to speak to others about how God has gifted them and how God might use them. We have the beautiful opportunity to encourage people along in pastoral ministry, even when they may not be able to see that possibility for themselves. We have the difficult responsibility to speak honestly to people when they’re pursuing this path but, if we’re honest, we don’t see it going well for them.

An important caveat: Can a community get it wrong? Yes! It’s good that Moses didn’t take the Israelites’ initial rejection––and ongoing rebellion throughout his ministry!––as final indication that he should quit. I don’t mean to suggest that a truly called pastor should never meet congregational resistance. The Christian community does not discern the will of God with perfect accuracy. And sometimes a Christian community can behave in outright wicked ways toward a pastor. I’ve heard the horror stories, seen a few, experienced almost none (thanks again to my wonderful community).

For people trying to discern calling

If you’re considering a calling into ministry, who is affirming that calling? Who is affirming it by investing in you and entrusting you with responsibility? Has a church or Christian organization already hired you and shown they want you to be on their team? Is anyone pushing you to go to seminary? Anyone ready to invest in it? If the answers to many of these questions aren’t positive, I would urge you to find a way to serve in a church or Christian organization, talk to people about how you can grow, seek opportunities for more and more leadership. Do that before you start spending on seminary. If you have trouble receiving those opportunities, you need to take those as potential red flags. Not yet dealbreakers, but cause for further investigation.

And if you’re struggling to identify a clear and certain calling to ministry, might you listen to the people around you more than yourself? Is it possible they’re seeing what plans God has for you more clearly than you’re seeing them for yourself?

A pretty close rendering of several conversations I’ve had:

Person: I’m just not sure I could do this. I don’t think I’m cut out for it.

Me: So, you don’t think you’re willing to do the work? Not up to the challenge?

Person: No no. I would do the work. But I feel like, Who am I to do this?

Me: So … you would feel like a fraud? An impostor?

Person: Totally!

Me: Are you living in a way that’s inappropriate for a Christian to live? Doing things that if people found out, they’d remove you from leadership?

Person: No.

Me: What are you hearing from other people?

Person: They keep encouraging me to take more responsibility. They keep giving me more leadership.

Me: Are you intentionally deceiving them? Have you told them you have qualifications you don’t actually have?

Person: Uh… no.

Me: So you need to know a really clear distinction: You are not an impostor. Impostors deliberately deceive people. They try to convince people that they’re something different than they really are. Fake medical degree. Falsified résumé. Hidden things in their lives. Impostors have too little concern for the damage they’re going to do. They’re reckless.

You are not an impostor. You have impostor’s syndrome. You’re overly concerned about the damage you could do. To the point that it’s preventing you from contributing what everyone else thinks you can contribute.

When you have impostor’s syndrome, the best thing you can do is quit listening to yourself and start listening to other people. Really, you need to listen to God. And right now, I expect the Christian community can hear from God on your behalf better than what’s going on in your own head.

Now, again, what are other people telling you about yourself?

That’s all on the nature of calling. Now let’s talk about the nature of ministry itself.

2 – Another perspective on ministry

The “don’t do it unless you can’t do anything else” line is usually a reference to toil and hardship. It suggests that the only thing that will get you through the suffering of ministry is knowing that God won’t let you do anything else.

Even more, some people have the impression that whatever God would call them to, it should induce misery. We have a sense that “taking up our cross” to follow Jesus means that God’s chosen vocation for us must be something we hate doing. So you’ll hear a lot of people say, “I know this must be God’s calling because I never would have chosen it for myself.”

How I’ve experienced ministry

I’ve had some difficult and painful moments in ministry––days, weeks, one or two years that were pretty brutal. Some of these will come no matter what you’re doing. Some are unique to the role of pastor. I’ll write some more about those in the future.

But far exceeding those moments are the moments of tremendous honor and privilege and blessing and joy.

People let pastors into parts of their lives that only a privileged few get to be a part of––some of the moments of greatest joy and greatest grief. We have the honor to sit with people as they prepare for a wedding and as they grieve after a death and prepare for a funeral. We have the awesome privilege of being sent to the Scriptures week after week to ask what’s there for us and our people, and then to announce to them what the text seems to be saying for us. We have the blessing of getting to pray with people through some of their hardest times and most important decisions.

My experience of ministry doesn’t fit well with the narrative of suffering for Christ. Moments of suffering? Sure. But defined by suffering? Hardly. My experience fits much better with the type of calling Eric Liddell references in Chariots of Fire. “I believe God made me for a purpose,” he says, “but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure.”

This is much less I’ll do it if I have to than it is I can’t believe I get to do this.

First Timothy 3:1 says, “Here is a trustworthy saying: Whoever aspires to be an overseer desires a noble task.” The words there are full of desire and delight language. What translates here as aspires is a word that’s translated in other places with craving or longing. What translates here as noble is translated throughout the New Testament as good or beautiful. First Timothy doesn’t treat the work of ministry as something to avoid unless you can’t. It treats it as something you might well desire and aspire to. Because it’s good and beautiful and delightful.

So for all the advice that says, “Only do it if you can’t do anything else,” I’ll suggest the opposite: If people will entrust you with this noble task, maybe you should do it … at least until you’re sure it’s not calling.

Like it or want to discuss? Most people find this blog because you share it. Thank you! Hit a sharing button below to share with others.