“I can believe in God without being a _________.”

How do you fill in that blank? Maybe you would use a word

like zealot or fanatic? Or maybe a less dignified word: freak, weirdo,

wacko, nut.

If you’re a Christian, does it mean you’re obligated to stand

on street corners with posters and a bullhorn? Or is it okay to be just an ordinary Christian?

Ordinary life presents us with plenty of challenges, long

before we need to go to any extremes. Before you consider standing on a street

corner with a bullhorn, you have to consider more pressing matters—how to get

along with a difficult friend or coworker, how to make ends meet in your

budget, how to take care of your children or your aging parents.

I love this verse from a paraphrase of the Bible, because it recognizes those ordinary parts of our lives: “Take your everyday, ordinary life—your sleeping, eating, going-to-work, and walking-around life—and place it before God as an offering” (Romans 12:1).[note]From THE MESSAGE: The Bible in Contemporary Language.[/note]

These everyday, ordinary parts of our lives can demand plenty

from us. I’ll give you a simple example. A friend of mine is a pastor in

Tennessee. A woman in his congregation antagonized him from the time he

arrived. Nothing he did ever seemed to be right. Every time he made a proposal

for something new, she rejected it and rallied others to her side. She had even

worked to have him fired. Their relationship was contentious at best, sometimes

closer to hostile.

And then her kidneys began to fail.

In difficult times, a pastor should be one of the first

people there alongside the person suffering. But how do you come alongside

someone and offer this kind of support after the relationship has been so

distressed? Should you be there when you know the person doesn’t believe you

should be the pastor at all? You may not have the kindest feelings toward her.

How do you offer sincere compassion and grace in a difficult time like this?

My friend’s dilemma was nothing extraordinary. It serves as just one simple example. These are the kinds of decisions we all face. How do we take the everyday, ordinary parts of our lives and respond in ways that are appropriate?

What I’ll suggest below is that monotheism—the belief that there is one true God—is more than a statement of belief. It’s a statement of devotion. And it impacts everything about our everyday, ordinary lives.

In the first of the Ten Commandments, God says, “You shall have no other gods before me” (Deuteronomy 5:7). What does that mean in practice—in our everyday, ordinary lives?

No God but One

Are Christians extremists? Can we believe in God without being zealots or fanatics or enthusiasts? Can we just be ordinary people, living ordinary lives, who believe in God?

I don’t think we can.

Any faith that takes seriously loving God with all––all of our hearts and souls and minds––leads to a single-minded devotion, the kind that will necessarily lead to extremism. In a world that has many loves—many gods that compete for some of our heart, some of our soul, some of our strength—those who instead devote all to God will appear extreme.

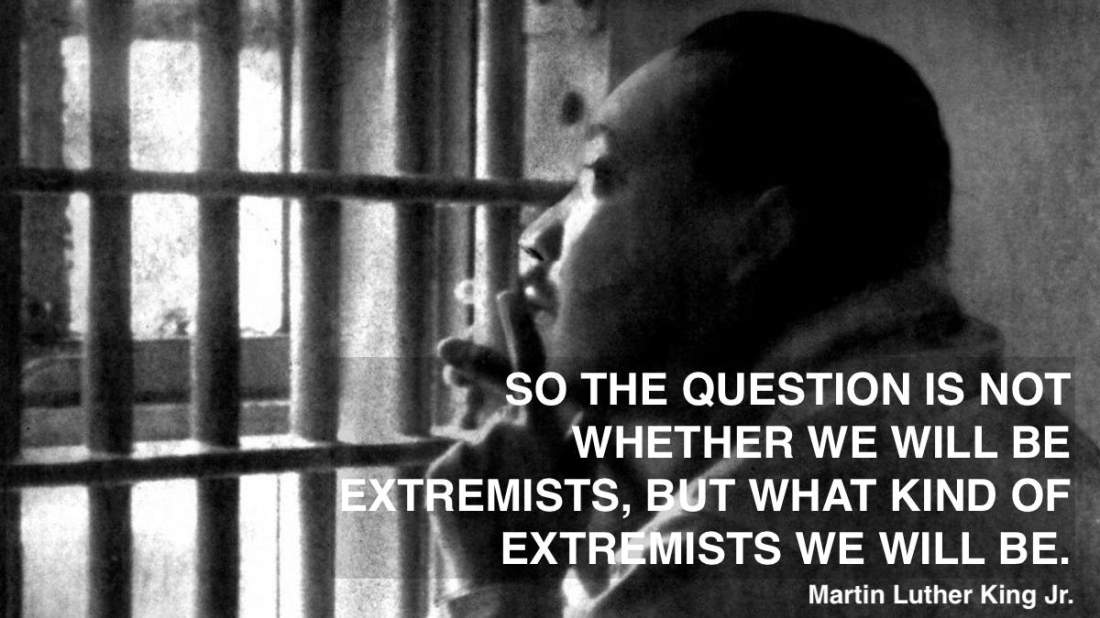

The word “extremist” is a dangerous word. I was wary of using

it at first, knowing that much of our world’s violence and terror are blamed on

“extremism.” Our remedy is often to avoid extremes, as if total devotion to

anything may be the problem. Look at this great quote to the contrary from

Martin Luther King Jr., in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” It’s a long

quote, but worth your time:

[T]hough I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime—the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment.

The call to love God with all is a call to extremism. The problem with the extremism that has so damaged our world was not extremism itself, but its misplaced devotion. Can you justify violence, hatred, or murder because of your extreme devotion to God? Not if your god is this God, the God who is compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in love. Not if you call “Lord” the one who said, “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you” (Luke 6:27). If you perpetrate violence or hatred because of your extremism, the problem isn’t your extremism, but your god.

Extremism: The key to a long and happy life?

But say you get your extreme devotion right. You devote yourself wholly to God—all your heart, all your soul, all your strength. Can we say that’s the key to a long and happy life? Maybe you’ve heard the popular saying: “God has a wonderful plan for your life!”

Note instead the serious consequences that may come with total devotion. Martin Luther King Jr. referenced seven people in that letter from a Birmingham jail. Jesus, Paul, and Abraham Lincoln were all killed. John Bunyan was imprisoned. Martin Luther was excommunicated from the church and his life seriously threatened. The details of Amos’ life are unknown, though one unauthenticated account says he was tortured and murdered. Only Jefferson escaped [relatively] unharmed after he penned the Declaration of Independence at great risk to his life.[note]He has also had many more questions raised about his character in recent years.[/note] And of course, King himself was assassinated five years after he wrote those words.

This shouldn’t be too surprising. Jesus warned his disciples about these things. After he told them that they were blessed for hungering and thirsting for righteousness, for being pure in heart and being peacemakers, he pronounced a more unusual blessing: “Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me” (Matthew 5:11). These are the likely consequences for anyone who would fully devote themselves to God: insults, persecution, and slander.

Now, let me follow that by saying something that may sound absurd. I still believe “God has a wonderful plan for your life!”

Extremism and the extraordinary

Martin Luther King Jr. called Jesus an extremist for love,

truth, and goodness. This is the true calling of all who would follow Jesus. We

who claim, “There is no God but one,” can do nothing less than devote all of

our lives to this God and what he commands.

In this, our everyday, ordinary lives become something more. A great theologian named Dietrich Bonhoeffer said it this way: “What is characteristically Christian is that which steps away from the world, rises above the world, is extraordinary.”[note]In Discipleship, volume 4 of Fortress Press’s Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works series, p. 146.[/note]

The extremist nature of our devotion to God may even add new options to otherwise ordinary decisions. Remember the friend I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter—the pastor whose church member was experiencing kidney failure? She had antagonized him for years, now how should he care for her in a time of need?

His answer went beyond the ordinary. He gave her his left

kidney.

I said above that I believe “God has a wonderful plan for your life!” That wonderful plan could cost you a kidney. It could cost you your wealth. It could cost you your dignity. And it could cost you your life. And yet we can call it wonderful, even if we might also call it difficult, or worse. It’s wonderful because Jesus says, “Whoever loses their life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 10:39). It’s wonderful because, in that extremist devotion to the way of God, we find true life. Our lives become rich and bold and empowered because we live and die to God alone.

———