How should the church interact with the culture around it? You’ve struggled with this question, whether you asked it in this particular way or not.

It comes in a variety of forms:

- Public policy issues (environment, economy, immigration, abortion, military …) –– Should the church openly support or reject certain positions? Should individual Christians vote according to their conscience? Should our faith influence our vote? Should we vote?

- Politicians — bless, endorse, denounce, or ignore?

- New musical styles –– appropriate for church use?

- Business techniques –– appropriate for church leadership?

- Pragmatics –– do the same codes of ethics apply in the world as in the church?

- The “secular” world –– throw all your Led Zeppelin CDs in the lake, or rock on?

I’m going to share two helpful models for making these decisions and then propose a necessary next step that I haven’t seen them take.

Christ and Culture

Have you heard of Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture paradigms? They’ve been the most prominent way for understanding cultural engagement questions since Niebuhr’s book Christ and Culture was published in 1951.

A brief explanation of his five categories:

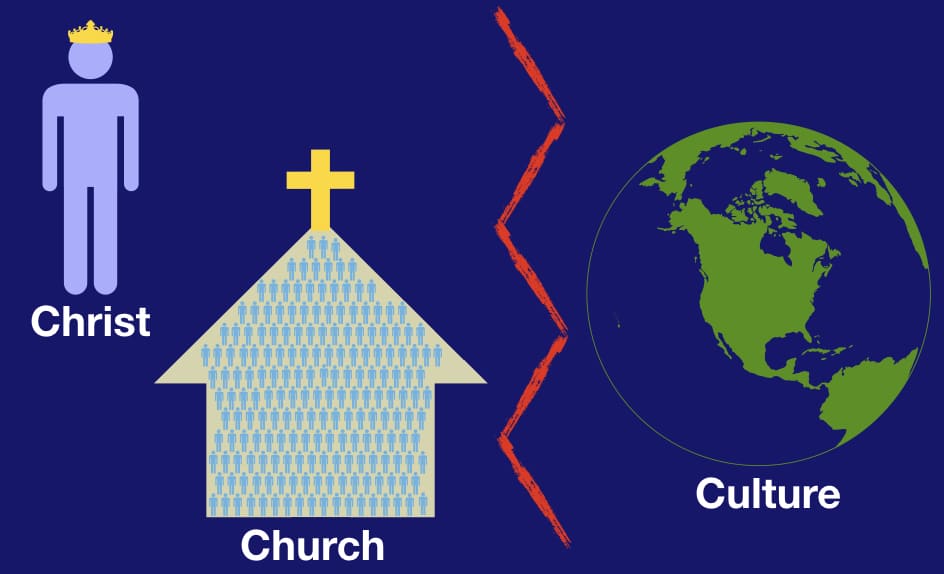

1 – Christ Against Culture – Christians should resist the world and its influences. It’s sinful, fallen, corrupted. There is a stark and necessary divide between Christ and the world. Anywhere you see Christians separating themselves from the world, you’re seeing a version of this model.

2 – Christ of Culture – This is the opposite of the one above. It says that God created everything, so we can expect to find God’s truth and goodness throughout creation. There is no divide between Christ and the world. Anywhere you see Christians talking about “plundering the Egyptians,” you’re seeing a view like this.

With these two we’ve set the poles. The other three fall somewhere in between:

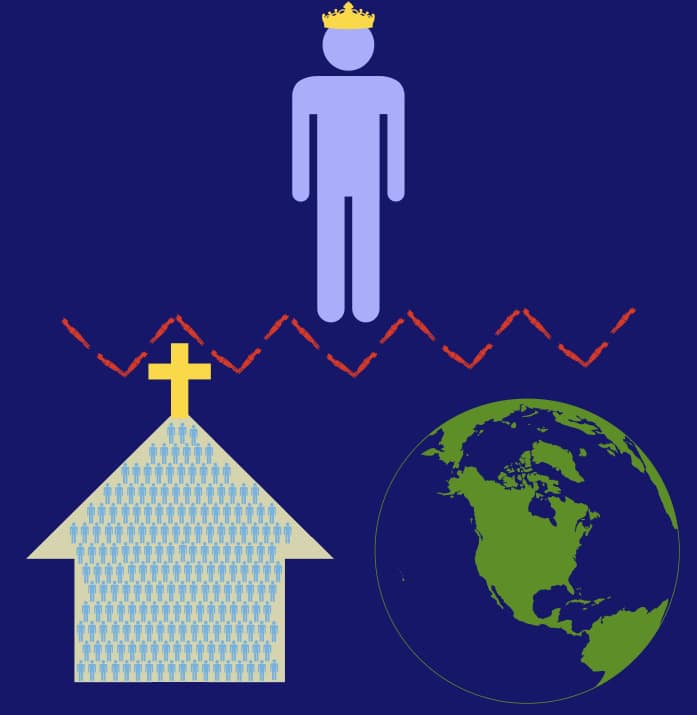

3 – Christ Above Culture – This is the both/and position. We don’t have to fully reject the culture as bad or accept it as good. Instead, we celebrate the good we find and reject anything contrary to the gospel. There’s a divide, but it’s not a complete divide like the “Christ against Culture” model.

In this paradigm, we also distinguish between a “secular” and a “sacred” world. God rules over both, but in different ways. So we can find God’s goodness in nature (secular), but we can only experience his full goodness through his supernatural grace (sacred). If you see Christians talking about submitting to the governing authorities in the world but also maintaining their Christian identity, it’s probably related to this view.

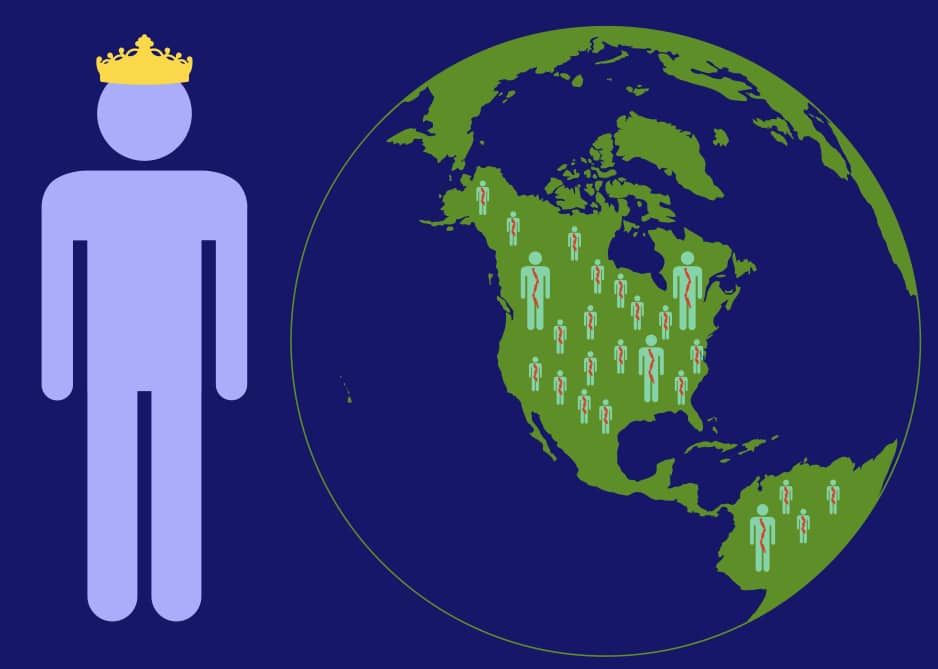

4 – Christ and Culture in Paradox – This is similar to the Christ against Culture position above. Except it doesn’t draw the line between a sinful, hopeless world and a holy church. Instead, it draws the line dividing good and evil “through every human heart,” as Solzhenitsyn described it. Each of us is a mix of good and evil. Ultimately, that draws the line between unholy people (all of us!) and God. The culture is not the problem. We are the problem.

In this model, humanity and God live in tension because all of us have both good impulses and wicked impulses, leading to both good and wicked expressions in our culture. Anywhere that we recognize that we’re totally helpless to save ourselves and that we have to trust in God’s grace, it’s a reflection of this model. As Paul said it, “What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!”[note]Romans 7:24-25[/note]

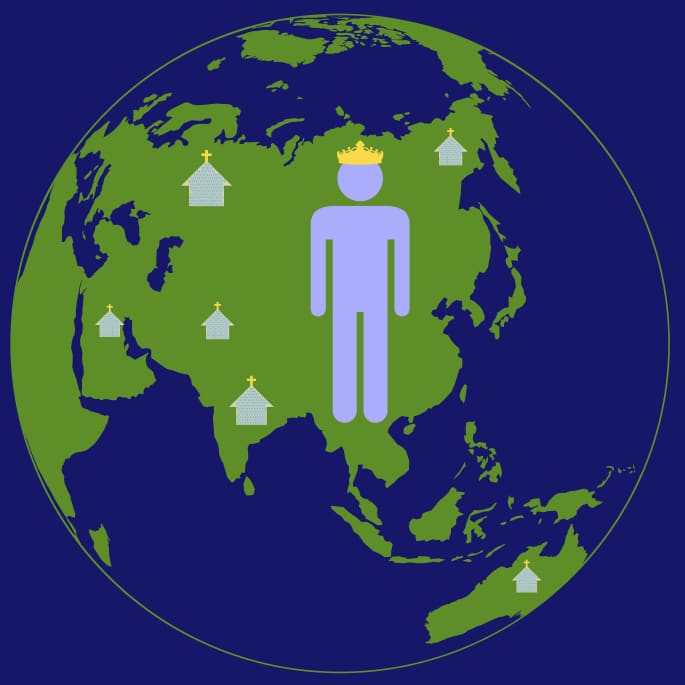

5 – Christ the Transformer of Culture – Like the Christ of Culture paradigm, this view understands God’s creation as good. But it recognizes the ways that evil has perverted that goodness. In this view, God is transforming his broken creation, restoring it to the original goodness he intended. And Christians can and should participate in that work. Anywhere you see Christians working for social change, it reflects this kind of understanding.

Keller’s extension

Tim Keller has contributed to this discussion in a way that helped me. He identifies our view of Christ and culture according to two questions.

His two questions:

- Should we be pessimistic or optimistic about the possibility for cultural change?

- Is the current culture redeemable and good, or fundamentally fallen?

That leads to this chart:

Very briefly:

The Relevance Model assumes the culture is good and that the church should be active in the world, so it finds ways for the church to learn from the world and catch up. You can see a lot of the “Christ of Culture” view in it.

The Transformationist View assumes the culture is not good and that the church should be active in the world, so it seeks ways for the church to transform the world. You’re thinking of “Christ the Transformer of Culture” here, right?

The Counterculturalist View assumes the culture is not good but that the church should not be active in the world. In this model, the church becomes a counter culture, an alternative reality to the model of the world. It’s a city on a hill, calling people in the world to come in, while avoiding being corrupted by the world. Another take on “Christ against Culture.”

The Two Kingdoms View assumes the culture is good but that the church should be separate from it. Think of separation of church and state. In this model, Christians participate as good citizens in the world and good members in the church, but we acknowledge that these are separate. This is most like the “Christ and Culture in Paradox” paradigm.

I didn’t list the “Christ above Culture” paradigm. It probably fits somewhere between “Two Kingdoms” and “Relevance.”

Which is right?

If these are new to you, take enough time to consider each of them. Then pick one. Is there one that best reflects your understanding of how the church should relate to the world?

Do you believe our primary stance in the world should be to work for positive change –– take our Christian worldview and seek to create a society that fits and follows that worldview? If so, you’d probably choose the Transformationist model.

Or do you believe our primary stance should be to celebrate God’s goodness as we find it already in the world –– to seek the common good? Then you’d probably choose the Relevance model.

Or maybe you think the primary stance of the church should be to serve as a shining city on a hill, a holy people in a fallen world, people who have others notice there’s something different about us and ask why. You’d choose the Counterculturalist view, if so.

Or finally, do you think you have an important but different role in church and world? We celebrate Word and Sacrament in the church; we do our work with humble excellence in the “secular” world. They’re very different worlds, and that’s okay. Then you’d choose “Two Kingdoms.”

Have you chosen your preferred model? The understanding you tend to use?

When I learned about these models, I began to understand what was happening in some of my disagreements. I was frequently coming to conversations about the church with a Counterculturalist mentality, and most of the people I was talking to were coming with a Relevance or Transformationist mentality. People had a hard time understanding why I would offer ideas about the church serving as an “alternate economy,” ask if it would be better if ministry were a bad career, suggest Christians pay less attention to elections, or deride pragmatism.

If you’ve had a hard time understanding or being understood in these kinds of conversations, perhaps the models explain why.

But which of us is right? Which is the proper model?

Keller answers that none is best. He says that we need to instead find balance. The answer is in the middle.

This is where I’ll disagree with Keller. Balance is often a mirage and rarely the answer. (The most annoying part of any discussion of Christian personality is when people get to Jesus and blather on about how Jesus is the perfect balance of all types — “He’s peaceful like a 9, a thinker like a 5, cares deeply about morals like a 1, bold like an 8…” Because how could we dare suggest Jesus had one actual personality, to the exclusion of others?)

In the case of cultural engagement, would we really advocate for “balance” across these four models in how the church handled the issue of slavery? In matters of human sexuality, slavery, and rock ‘n’ roll, does a balanced use of all of these models achieve what we need to? I don’t think so. I don’t think we can, or should, treat sexuality, slavery, and rock ‘n’ roll the same. They each require a different kind of Christian response. But how do we choose?

I find that we usually choose the model for each particular issue that we like most. This allows us to justify almost any response to any issue. And perhaps we call that “balanced.” But I think we can do better. In my follow-up post (now available here: “The church in a (once) sexually-liberated world”), I’ll try to extend these models to a more helpful use. For now, I’d be interested to hear your thoughts and questions about the models outlined here.