Kanye West tweeted something that many of Christianity’s greatest theologians would agree with…

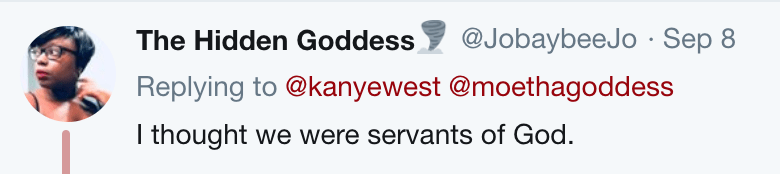

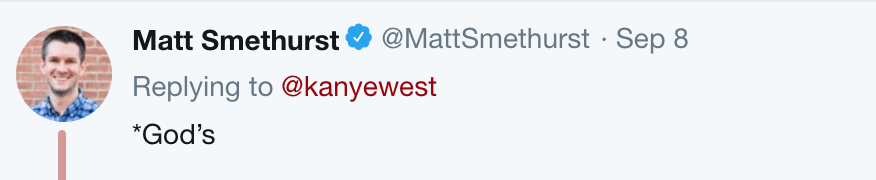

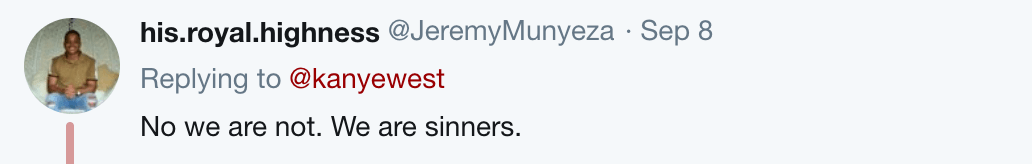

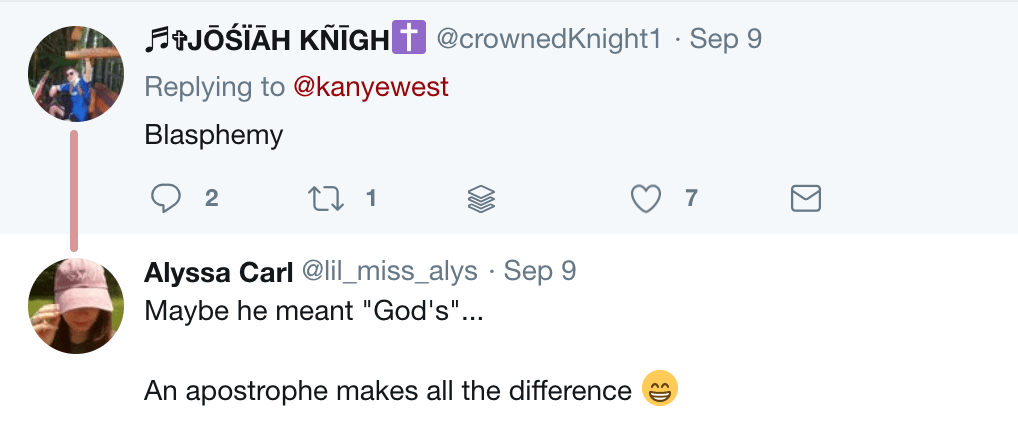

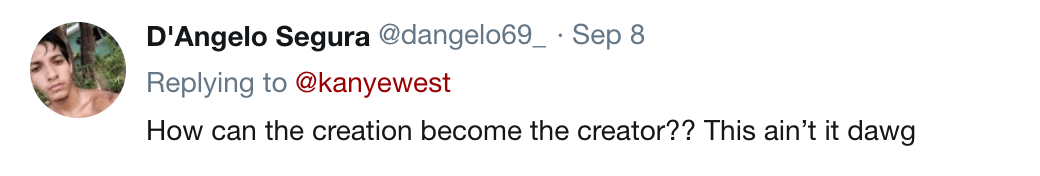

And Christian–or at least theistic–tweeters rebuked him…

To be clear, I doubt Kanye intended what those Christian theologians intended when they said the same. But what if his words were actually orthodox Christian belief?[note]Best to make that “g” lower case[/note] It’s a belief that we’ve mostly lost along the way, and as a result, we’ve lost a lot of the richness and depth of Christian experience. Let’s take a quick look at our relationship to God, as depicted in the Bible and the early church.

Sharing in the Life of the Father

Jesus tells a parable many refer to as the Parable of the Prodigal Son.[note]Find it in Luke 15:11-32[/note] A son asks his father for his inheritance, then leaves his father’s house and squanders it all. He ends up so destitute that he longs to eat even pig slop. Finally, he returns to his father, hoping to receive a position as a servant in his house. The father receives him back, but as his son, not a servant. And the father throws a feast. His son has returned—kill the fattened calf!

The story closes with the father consoling his other son, who refuses to come in to the feast. The older son is upset—how could his father have a feast for the one who squandered his inheritance when this obedient son has never even had a young goat for a party with his friends? The father responds, “You are always with me, and everything I have is yours.”[note]Do you recognize that? It sounds a lot like when Jesus says, “All that belongs to the Father is mine.”[/note]

Neither son has understood his real inheritance. It’s not what they can receive from their father to enjoy on their own. The inheritance begins now—it’s sharing at the feast of the father! Everything he has is theirs! Now!

This makes me wonder if I usually look for God’s “blessings” in the wrong places. I look for how God is benefiting me, making my life better, providing the right opportunities. These “blessings” are about what I can receive from God to enrich my own life. Like the brothers in that parable, I may misunderstand the real inheritance when I watch for these as God’s blessings.

What a wonder! God invites us to participate in the divine life as his children. He invites us to his table. He invites us to share everything he has.

An important distinction: the inheritance isn’t just to take what the Father gives, but to share what the Father has.

If our real inheritance is to share what our Father has, it means we can share in God’s perfect love and holiness and joy and peace. We share in God’s divine nature.

Union with God?

This is where some theologians have talked about a sort of union with God that would sound unthinkable to many Christians. One of the greatest early Church Fathers wrote, “If the Word became a man, it was so men may become gods.”[note]From Irenaeus in the preface of Book V in Against Heresies. To be sure, this is the universal use of “men,” males and females are included equally in it.[/note]

Did you gasp reading that? We might be quick to respond, “There is no God but one!” We are creatures, not the Creator.[note]The difference between God (Father, Son, and Spirit) and humanity is that the Father eternally begets the Son and brings forth the Spirit from his very own substance. But God created humanity in time from nothing. We retain our human nature, even if we might be called “gods” or “one with God” as we participate in the divine nature.[/note]

That will never change. Those theologians would certainly agree. But we can become so united to God that we share God’s will and thoughts and actions. We can be so united to God that we become holy as God is holy. One New Testament letter refers to this as “participating in the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).

In Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis comments on it like this:

The command Be ye perfect is not idealistic gas. Nor is it a command to do the impossible. He is going to make us into creatures that can obey that command. He said (in the Bible) that we were “gods”[note]A note: God really does call people “gods” in the Bible. You can see this in Psalm 82, and then as Jesus refers to it in John 10:34-35.[/note] and He is going to make good His words.[note]On page 205 of the 2001 HarperCollins edition.[/note]

Notice how much more this is than the standard ways we think of life with God. Some people talk about “inviting God into your life” or a “God-shaped hole” that reveals our need for God. But God’s invitation goes infinitely beyond his entering into our small lives or filling some particular hole or desire in our lives. Instead, God’s invitation is that we would come into his divine life. This doesn’t so much fill a particular hole as it consumes the whole of us. It consumes the whole of us to the point that we would be called fully God’s, and by being God’s, we would actually be called <gasp> “gods.”

An early Christian theologian named Augustine famously wrote of God, “You have formed us for yourself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in you.”[note]From the first paragraph of Book I in The Confessions.[/note] He didn’t say our hearts are restless until they find a place for God, as if we should have God take a seat at our table. Instead, our hearts are restless until they find rest in God, until we are seated at the very table of God.

The problem when we decide to have life our way isn’t just that it’s sin—some sort of disobedience to our Father. The greater tragedy is that while we indulge our small desires, it’s as if we’ve chosen pig slop when we could instead be feasting at the table of God.

What if Kanye is right?