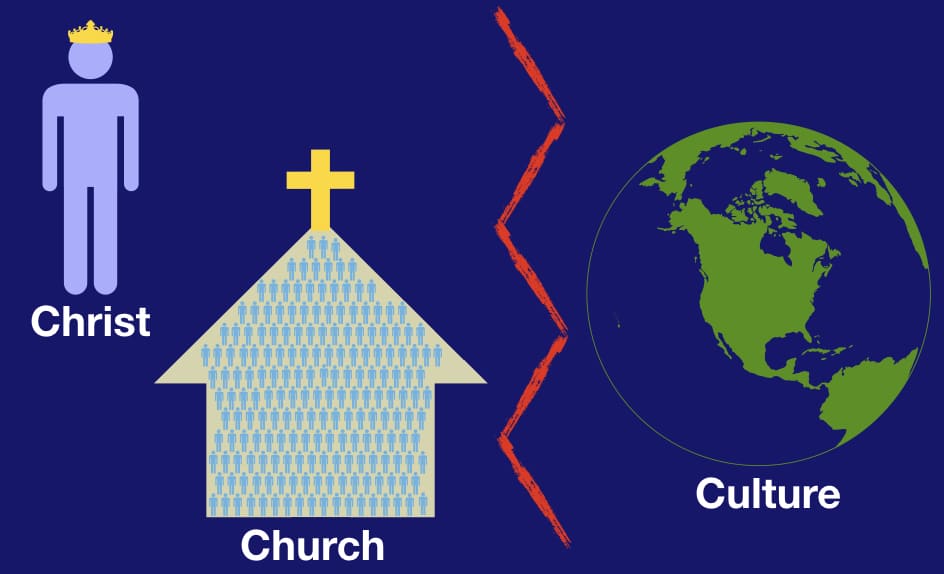

In the past two posts (see here and here) I’ve been discussing how the church engages with the world. I shared two popular models that try to describe our options.

We can take a “Christ of Culture” / Relevance approach to the world and assume what we see in culture is good, relevant to the Christian life, and should be embraced.

We can take a “Christ against Culture” / Countercultural approach and assume what we see in culture is bad, harmful to the Christian life, and should be rejected.

Or we could take a mediating view. You can see more about those in the previous posts (again, here and here).

Here’s Keller’s model again. It asks whether the world is generally good or bad (how full of common grace?) and whether the church should be active or passive in influencing culture.

The problem with the models

These different models for how the church and Christians can engage culture are helpful descriptive models. But they’re flawed when we begin to use them as prescriptive models. We can’t begin with a “Relevance” mindset, for instance, and assume that we can apply it to everything we see in our culture. As I concluded in my last post, whatever perspective you take on how the church engages with our culture on sexuality, you almost certainly wouldn’t maintain the same position with slavery and rock ‘n’ roll. No one model fits all situations well.

This is where Tim Keller advocates balance––we should move toward the center and not go too extreme in any direction. But “balance” isn’t enough help, and it’s not always right. We celebrate that William Wilberforce didn’t take a “balanced” approach to the injustice of slavery.

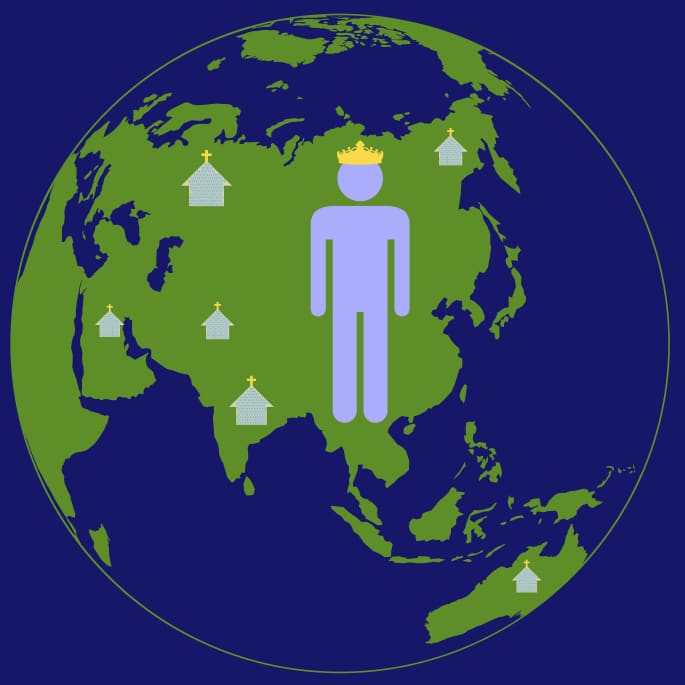

A Prescriptive Model: Christ in Culture

The models we use for Christ and culture say too much. They try to claim Christ has a single position relative to our culture: of, against, above, transforming … But the reason we have all of these models is because we see that Jesus took all of these positions in his first century culture. And as the Body of Christ, the church does the same, or should. We should understand ourselves as the Body of Christ in culture––sometimes adapting, sometimes rejecting, sometimes transforming, etc.

I’m going to propose that we use love as our guiding principle for engaging culture. Novel, right?

More specifically, let’s use Jesus’ great commandment as our first guideline. Jesus says, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”

Everything we do should be aligned to loving God and loving God’s creation.

[I’m taking a liberty here to use “creation” instead of neighbor. “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it.”[note]Psalm 24:1; 1 Corinthians 10:26[/note] All people, creatures, and creation. He has given it all to us as a gift. Use the comments if you disagree with me.]

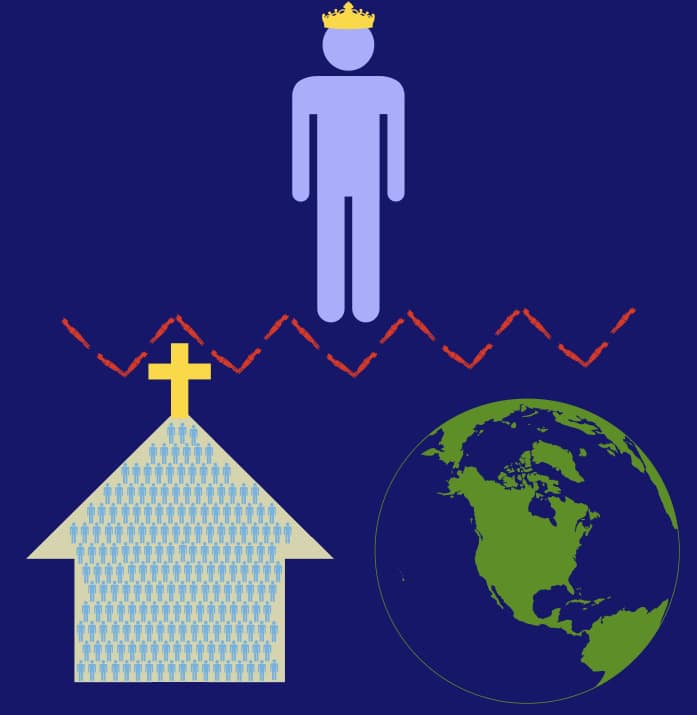

So now we can expand on what we mean by love. We’ll draw it out like this:

Notice that this isn’t like some of the other questions we’ve seen about cultural engagement. It doesn’t ask us to claim which is the right way of viewing things, as if one side of the pole is right and the other wrong. It asks a situational question instead: “Are we talking about love of God or love of God’s creation in this situation?”

To be clear, these are in many ways inseparable. If the creation is God’s precious gift to us, we can hardly abuse that gift while loving God. And our ability to love comes from God. Nevertheless, some questions primarily have to do with how we relate to God and others with how we relate to others.

It won’t be enough for us to talk about love, though. Love takes different forms, and these will come into play. Here’s how we see it described in Romans 12:9 – “Love must be sincere. Hate what is evil; cling to what is good.”

So let’s draw a second line:

That looks a lot like Keller’s four quadrant model above. But it doesn’t ask us for our generic approach to the culture. It asks for our specific approach to every issue that presents itself.

How do we engage the culture in each of these quadrants?

Bless the Good

Take a look first at that upper left quadrant. What does it mean to “love God’s creation” and “cling to what is good”?

It means blessing and delighting in God’s good creation. The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it. He created it and called it good. We continue to see God’s goodness in his creation. And wherever we see it, we should celebrate it.

This may be the quadrant that “evangelical” Christianity has most neglected over the past several decades. It’s the reason many Christian teenagers have come away from the church with generally negative views of sex as something dirty, shameful, and sinful. (Just search “purity culture.”) It’s the reason many people view the church according to what it stands against.

The Church –– and especially evangelical Christians –– could stand to spend a lot more time in this quadrant. What do we see and celebrate as good in God’s creation? How can we name and bless and delight in what is good?

If you read or listened to my interview with Mike Mather (here and here), this defines well what he’s doing. The “Relevance” and “Christ of Culture” models find their roots in this quadrant.

When we bless the good, we focus on goodness and beauty. We recognize these as attributes of God and God’s creation. The Western Church has undervalued beauty in recent years. N. T. Wright talks about beauty as part of the three-fold mission of the church, along with justice and evangelism.[note]See ch. 13 of Surprised by Hope.[/note] I doubt most of his readers would have been surprised to see justice and evangelism on that list. But I bet few of them expected to see beauty there.

Seek Justice

Look now to the bottom left quadrant. What does it mean to “love God’s creation” and “hate what is evil”?

Above all else, we believe that everyone is created in the image of God. Everyone. And where people are oppressed, neglected, or treated in a way that denies their dignity, justice is perverted.

Wherever God’s good creation is treated without dignity, it’s unjust. The Christian response: seek justice.

You’ll find wings of the Church that hold this as their primary concern and others that have neglected it. Where we’ve done well, we’ve defended those who were abused and taken advantage of. We’ve taken up the cause of those who have been deprived of power and pled the case of those who have been deprived of voice.

I discussed both the #MeToo movement and the abolition of slavery in the previous post. If those are movements you believe Christians should have celebrated and taken part in, it’s because of a sense of justice. To many people’s surprise, evangelical Christianity has a long history of activism, including the abolition of slavery, fighting for the poor, and women’s rights. I’ve written about that in more detail here.

Where we get things wrong with seeking justice, we make two opposite mistakes. One mistake is to ignore it. That happens when we discount the value and goodness of God’s creation and focus entirely on salvation. We feed people’s souls but neglect their bodies. We point to God’s kingdom in the future without regard for God’s will done on earth, as it is in heaven.

In the other instance, we mistake ourselves for saviors and use language about “building the kingdom,” usually through our own revolutionary tactics, as if it were ours to build. We can act as if we “want the Kingdom without the King,”[note]In Mark Sayers’s brilliant parlance.[/note] doing it all ourselves with little attention to Christ.

You’ll also find occasions where we fight for justice with such rabid force that we oppress, neglect, or deny the dignity of another person or group in the process. Look to the current state of politics in the United States and across the Western world, and I believe you’re seeing opposing social revolutions. Both are giving attention and voice to groups that have long been ignored and excluded.[note]See the increasing progressive focus on race, gender, and sexual identity. See also the thesis of President Trump’s inaugural address: “The forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer.” His surprising victory came because of his unique appeal to small town voters, mostly white people without college educations, long neglected by both political parties and unrepresented in our nation’s elected leadership.[/note] Meanwhile, their seeming hostility toward another long ignored and excluded group grows. One of the greatest idolatries of our time––partisan politics––threatens to deny some people justice in its fervor for justice for others.

The “Transformationist” and “Christ the Transformer of Culture” models find their roots at least partially here. When we seek justice, we focus on God’s nature as a just God who will set his world to right.

Be Holy

We move now to the upper right quadrant. What does it mean to “love God” and “cling to what is good”? I’ve chosen “Be Holy” as the way to represent this. We could also use language here about worship or devotion. This is about clinging to God, because God is good.

I’m using language of being and holiness because this quadrant isn’t just about what we do; it’s about who we are. When you hear anything about “being holy,” your mind likely goes to something like rule-following. But holiness is much bigger than that.

Throughout the New Testament, we encounter the incredible claim that we are united with Christ. This was the premise of my serious post with a tongue-in-cheek opening: “We are gods.” What if Kanye was right? Or see this helpful article: “10 Things You Should Know about Union with Christ.”[note]It’s written through the lens of Calvin’s theology. My discerning Wesleyan readers might pick up on that in a few places. I think it is overall a very good, agreeable representation. Use the comments if you take issue with any of its claims.”[/note]

Holiness is not so much an expectation of who we should be as it is good news about who we can be. It’s not so much God’s requirement of us as it is a calling, a possibility, God’s very design for us. And if God has designed us for holiness, he will surely do it in us.

We’re God’s holy people, set apart for God and set apart from sin.

In my previous post, I suggested that Christians have the option to look to our culture for our sexual ethics: don’t make such a big deal about casual sex, casual nudity, extramarital sex. If you objected to that approach, it was probably because of this notion of holiness. By the grace of God, we’re a set apart people. We give that up when we follow whatever the world tells us is okay. It’s specifically regarding sexual ethics that the apostle Paul reminded us that we’re united with Christ: “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ himself? Shall I then take the members of Christ and unite them with a prostitute? Never!”[note]1 Corinthians 6:15[/note]

Some people may view Christians as prudes or holier-than-thou or self-righteous because of our moral stances. If we come off that way, it may be because we’ve misunderstood holiness. Holiness is not about being better than other people. It’s not about looking down on others. It’s not about following unnecessary rules. None of these would describe Jesus as we see him in the gospels. And yet we say that Jesus is fully holy––unerring in his devotion to the Father, neither looking down on others nor condoning sin, the model of prudence.

The “Counterculturalist” and “Christ Against Culture” models find their roots in this quadrant. They recognize that Christians live our lives devoted to God, even in union with God. Compare that to this from 1 John 2:16, “For everything in the world––the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life––comes not from the Father but from the world.”

With holiness, we encounter one of the biggest differences between the Church and the world. At your business, should someone be eliminated from consideration for leadership if they aren’t a devoted Christian? In almost all instances, the answer is no. But in the church, should devotion to God––marked by holiness––be prerequisite for certain positions? Yes!

Speak Truth

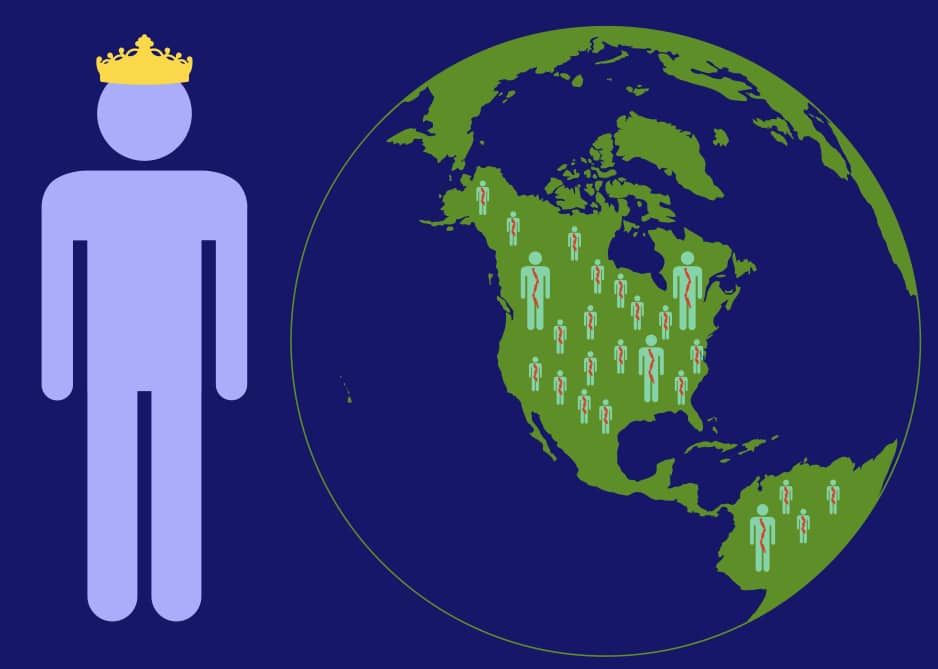

I think there’s another reason some people accuse Christians of being holier-than-thou. (To be clear, I’m not discounting the first problem: that we really can behave that way.) That other reason is that Christian holiness can unveil idolatry. And no one likes their idolatry unveiled.

Take a look at that bottom right quadrant. What do we get when we cross “love God” and “hate what is evil”? What we should hate is when something or someone other than God is worshiped. We call this idolatry (turning something else into our god) or heresy (misrepresenting the true God).

How do we engage a culture that worships other gods and misrepresents the true God? By speaking truth.

We see Jesus and the apostles speaking truth in these kinds of ways throughout the New Testament. In addition to the compassion and grace Jesus extends to the Samaritan woman in John 4 (because all people are created in the image of God and to be treated with dignity––Bless the Good), Jesus also says, “You Samaritans worship what you do not know; we worship what we do know, for salvation is from the Jews.”[note]John 4:22[/note] It’s a claim about who the true God is, spoken against a false notion about God.

Paul’s speech in Athens does the same thing: “You are ignorant of the very thing you worship––and this is what I am going to proclaim to you. The God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands.”[note]Acts 17:23-24[/note]

Do Jesus’ and Paul’s words here seem abrasive? Unkind or uncaring? They weren’t received well by all who heard (some who heard Paul sneered at him), but others responded with belief. Their false worship of other gods turned to true worship of the living God.

We have no fewer idols today than they had then. We likely have more. Christians today need to continue unveiling idols and heresy for what they are. There will be many methods, and I would advocate the more winsome ones as best––ones that don’t forget the dignity of the other person. But if we abandon any effort to speak truth in our world, we’ve abdicated the Church’s ongoing call to proclaim the good news.

The “Transformationist” model also has some roots in this quadrant, along with the “Seek Justice” quadrant above. That’s because truth-telling and justice-seeking are different means of transforming our culture. In both, we must be careful not to ignore the dignity of those whose hearts, minds, and behaviors we seek to change.

Most of our idols today are not bad things. They belong in that upper left quadrant. They’re good. But when they take the wrong place in our lives, they cease to be goods and become gods.

Problems with this model

This model won’t answer all our problems quickly or easily. The big question it doesn’t answer: What is good and what is evil?

Niebuhr’s and Keller’s models allow us to start with an assumption about good and evil in the world. We either expect the things we encounter to be good or we expect them to be evil. Of course, the problem with those models is that our assumption will often be wrong. Not all things in our culture are good. Nor are they all bad.

So this leaves us to do the hard work in an ever-changing culture. And we’ll frequently find that a question requires us to work in all four quadrants. For instance, the church’s swirling debates about human sexuality involve human dignity, justice, holiness, and truth. How do we go beyond holding these in a weak balance to observing each to its fullest?

Lots more still to consider. For now, go and Bless, Be, Speak, and Seek.

See the next post in this series here: “Blessing and Delight: Goods and gods, pt. I”

Did you think this was helpful? If so, PLEASE share it with others. Social media, email, word-of-mouth. However you share things. Click here for Facebook sharing. Or here for Twitter sharing. Or here for LinkedIn sharing. TikTok sharing is unavailable.