In the coming years, the church must find a way to maximize its resources. The United Methodist Church serves as an excellent experimental lab, with thousands of ongoing experiments running in different local churches and Annual Conferences. What can we learn from those experiments? In the last part of this series, I detailed why we need to focus on church planting. This part will focus on the how.

Church Planting

Over the past 200 years, Methodists planted over 800 self-sustaining churches in the state of Kentucky. Those churches have been places of care for their members, mission outposts in their communities, and contributors to a mission far beyond their own.

How can we continue to create places like these for future generations?

I’ve read numerous studies on church planting and conducted some of my own research over the past few years. The most slap-you-in-the-face clear findings: (1) more churches reach more people [see previous post]; (2) initiatives sponsored by local churches usually succeed; the rest usually fail; (3) disproportionate outside funding harms long-term sustainability.

Local Initiatives

One of the best quantitative studies I’ve found analyzes the Christian Reformed Church’s planting success. It compares local initiatives to denominational initiatives. Of the 43 locally sponsored initiatives, 31 were successful, a 72% success rate. Of the 36 other initiatives, 2 were successful, a 94% failure rate!

The author of the study, David Snapper, discusses advances in church growth research and training for church planters. Many people expected good training in church growth techniques would lead to success. However, the denominational-initiative pastors––the 94% failure rate pastors––had received heavy training in church growth techniques. Snapper concludes, “[G]ood technique cannot, by itself, overcome the enormous difficulties imposed by isolation, lack of support, diminished name-recognition, and similar realities of many NCDs.”

Of course, this study was conducted on congregations organized between 1987 and 1994.[note]See “Unfulfilled Expectations of Church Planting” by David Snapper in the Calvin Theological Journal 31 (1996): 464:86.[/note] A lot has changed since the 90’s. Is this data still relevant? Results from recent Kentucky church plants suggest that it is.

I wish our team in Kentucky had come across Snapper’s research study and heeded its warnings fourteen years ago. A study of UMC church planting in Kentucky from 2004-2018 showed similar results. We looked at all plants that had received denominational funding in the past 14 years and have since gone off funding. We categorized them as no longer existent, sustaining,[note]exists, but is not paying denominational apportionments, a sign of continuing financial challenges[/note] and thriving.[note]financially self-sustaining + paying apportionments[/note]

Out of fourteen attempts at independent plants, eleven no longer exist and three are sustaining. None were categorized as thriving. That makes for a 21% somewhat-success rate.

Out of ten attempts at local-initiative plants––multi-sites or plants from a founding church––two no longer exist, three are sustaining, and five are thriving. That makes for an 80% success rate for at least sustaining, 50% success rate for thriving. The two that no longer exist represent one idea that received limited funding and never actually began and one congregation that left the UMC denomination (so they do still exist, just not in the UMC).[note]I’m not including other kinds of plants that were a part of the larger study––multi-language plants (new language, same location), church restarts, and church-within-a-church. Our sample size was too small and results too inconclusive to be of much help. The early results from all of those did not look good.[/note]

Every piece of our findings confirms what that earlier study of the Reformed Christian Church demonstrated: Initiatives sponsored by local churches are likely to succeed, the rest are likely to fail.

As with frequent moving of pastors, the independent plant model of church planting seems to defy basic biology. A church plant is much more likely to succeed as an organic outgrowth from an existing church than as an isolated strategic initiative. God can create ex nihilo. The rest of us will do better with the strong base of support a local church provides.

Disproportionate Funding

Another question we asked about church plants over the past 14 years: How did the amount of denominational funding they received impact their long-term success?

Specifically, we asked, “For every dollar given by church members during a new church’s first year, how many dollars of denominational support did they receive?” Many of us expected an easy answer: the more financial support, the better. That was wrong.

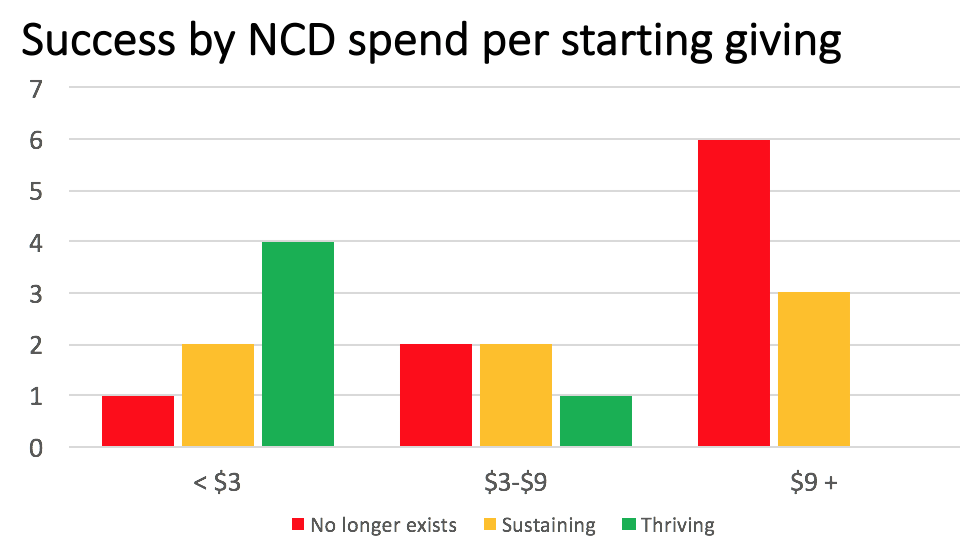

We categorized them into churches that received <$3 in total from the denomination for every dollar contributed by members in the first year (e.g. If a new church’s giving was $50,000 in its first year, the total denominational support was $150,000 or less), churches that received $3 – $9 for every dollar contributed by members, and those that received over $9. Look at the success rates:

The more disproportionate the denominational support, the less likely a new church was to succeed.

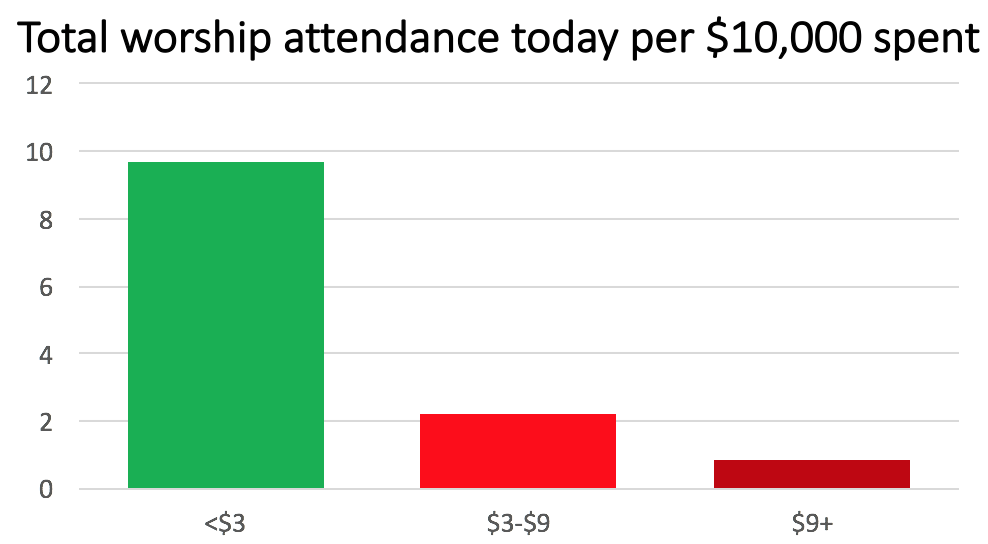

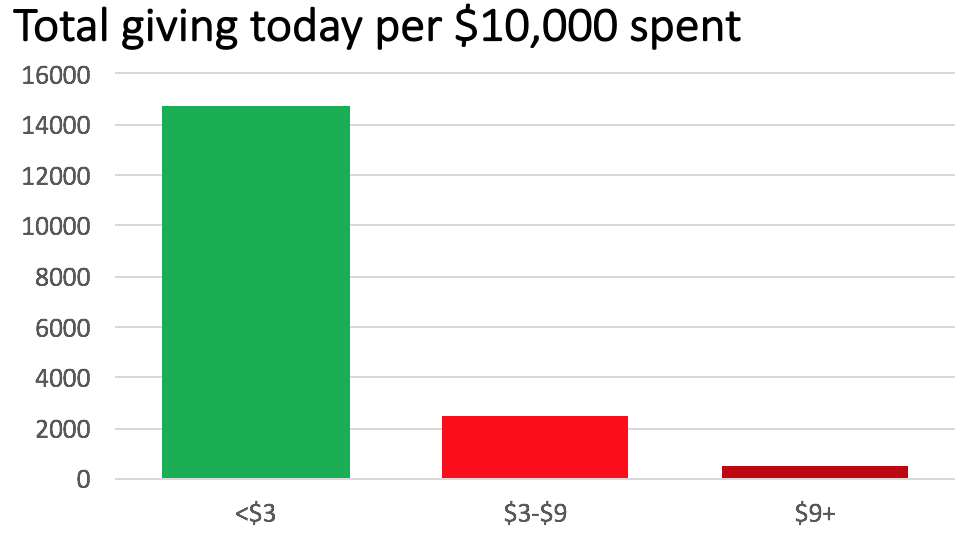

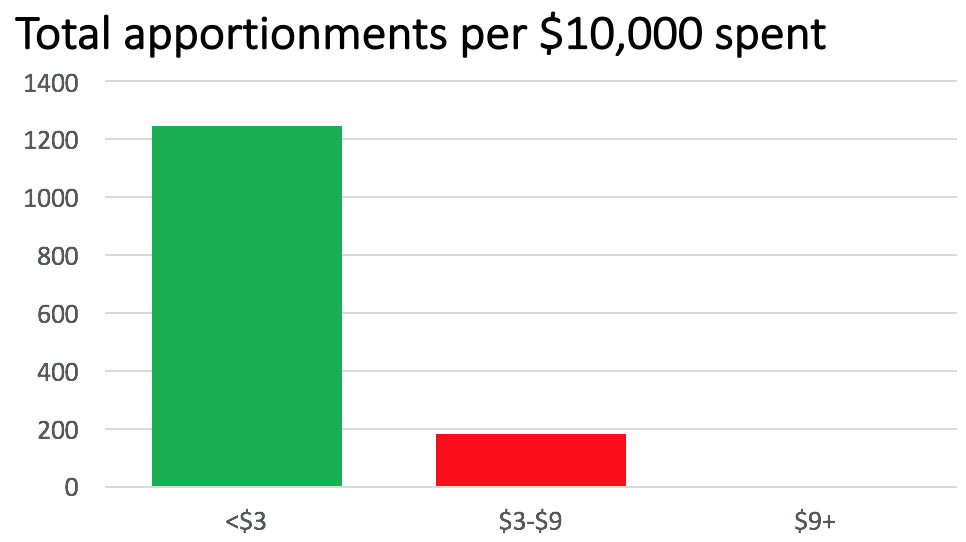

Even more revealing is a look at attendance, giving, and contributions back to the denomination (“apportionments” in the UMC) for each of these categories. We asked, “For every $10,000 our denomination invested, what is the average worship attendance––or annual giving, or annual apportionments paid––today?”

To help make sense of this chart –– The churches that received a total of <$3 from the denomination for every dollar of first-year giving are averaging nearly ten people in worship per $10,000 invested by the denomination. If the UMC invested $100,000 in one of these churches, attendance today is likely around 100 today. By comparison, if the UMC invested $100,000 in a more disproportionate way –– if it was in the middle category, that church is likely to have 20 in worship today.

I think what we’re seeing here is that with more disproportionate denominational investment, new churches become dependent on that funding. They are unable to mature into churches that can become self-sustaining.

This runs against much of the logic used in new church development circles. If a church has more internal funding, we support them less, supposing that they have enough already. If a church is struggling financially, we often rush to their aid with more denominational funding, trying to prop them up. Those efforts to prop up will probably be wasted money, keeping a new congregation dependent on the denomination, when it would be better to allow them to either rise to the challenge or close.

Putting it all together

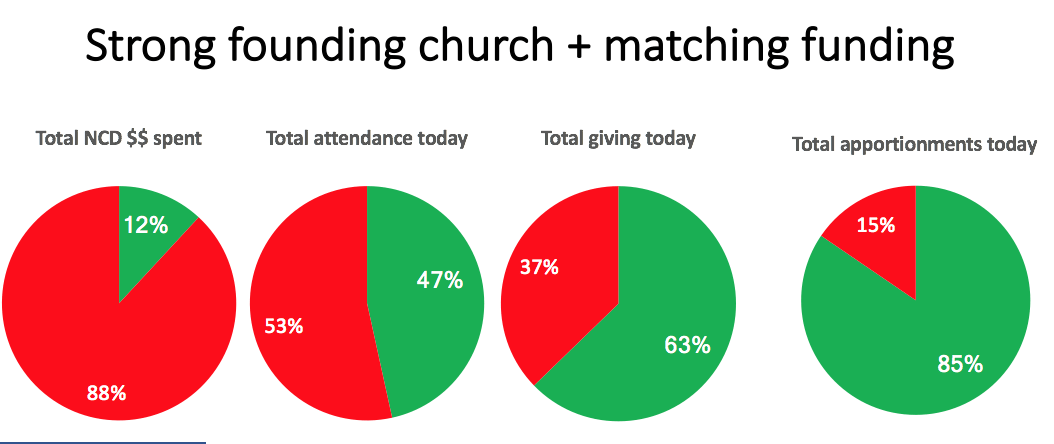

What if we asked only two questions for supporting new faith communities: (1) Is it an initiative coming out of a strong founding church? (2) Can we support it with proportionate denominational funding? In this case, I’ve identified proportionate as matching funding from the denomination that would put a church in that <$3 category above.

In the past 14 years, 12% of Kentucky investments in new church planting have fit those two categories. Look at how those investments have done:

I think we have enough evidence to make a change. We should re-focus our church planting resources. Can a good idea + a charismatic leader + massive denominational funding lead to a successful church plant? Of course! But it will be the rare exception to the rule. We’ve spent millions on parachutes for charismatic leaders with good ideas, and we have little to show for it.[note]This should actually provide some reassurance to any of those discouraged leaders. If you tried to start a church without the strong backing of a local church and were unsuccessful, we shouldn’t first assume it’s a reflection on your leadership. The odds were stacked against you.[/note]

Denominations need to keep a focus on church planting, but their role needs to be about inspiring and incentivizing local churches to plant new churches. Denominations should invest in those new plants as partners, not as their primary benefactors. We need to get out of the business of investing in ideas––even ones with exciting, well-crafted plans. We need to run from any notions of centrally-planned initiatives. If we continue investing in initiatives that aren’t based out of a local church or where denominational funding makes up most of a new church’s budget, we need to ask whether we’re squandering our resources.

I don’t want you to miss the next post, and neither do you. To be sure you don’t miss it, JOIN my e-mail update list.

Look at that beautiful direct relationship. More churches = more people in worship.

Look at that beautiful direct relationship. More churches = more people in worship. No relationship. The correlation is -0.12. This doesn’t change significantly even if we separate our counties by size. Even among our large counties––where churches are likely to grow larger––the number of churches per capita relates to how many people we’re reaching, the average size of the churches in that county does not.

No relationship. The correlation is -0.12. This doesn’t change significantly even if we separate our counties by size. Even among our large counties––where churches are likely to grow larger––the number of churches per capita relates to how many people we’re reaching, the average size of the churches in that county does not. When we look at our merger products, we see more evidence that our bigger is better thinking is flawed. Analysis of Kentucky’s merger product churches over the past decade shows them as the single worst-performing category of churches we found. We had eleven merger product churches. Nine declined in their combined attendance and averaged a 33% loss. Five of them were among our top 20 attendance decreases across the conference during this period. (A category of churches that makes up only 1.4% of the Conference represented 25% of our churches with worst worship attendance losses.)

When we look at our merger products, we see more evidence that our bigger is better thinking is flawed. Analysis of Kentucky’s merger product churches over the past decade shows them as the single worst-performing category of churches we found. We had eleven merger product churches. Nine declined in their combined attendance and averaged a 33% loss. Five of them were among our top 20 attendance decreases across the conference during this period. (A category of churches that makes up only 1.4% of the Conference represented 25% of our churches with worst worship attendance losses.)