Last year, I attended a conference where a leadership group shared about the massive failure of their church planting strategy over the past decade. Massive, in their case, was around $15 million spent with almost nothing to show for it.

This was at a conference about using statistical data to measure our outcomes. (A friend called it “nerd camp.”) It was refreshing to hear a group of leaders admit to their past mistakes –– well, the mistakes of the previous regime, but still…

Then the presentation shifted to their new plan. They talked about the millions of dollars they were planning to invest in new efforts. Fresh Expressions. Closing dozens of churches to create “vital mergers.” They spoke with assurance and excitement about the great things that were about to happen in their conference because of this grand new strategy. Most people in the room –– composed mainly of Conference leadership from across the United Methodist Church –– seemed inspired and excited by this bold new vision.

One question gnawed at me: A decade ago, couldn’t that previous team that blew $15 million have stood on stage somewhere and talked about their bold and exciting new vision to plant churches?

In fact, that leadership team a decade ago probably did just that. They probably shared their vision with leaders from other areas who walked away inspired and wishing that their leaders could dream such big dreams and cast such big visions.

So what made this new 2017 leadership team so confident that they would fare better? We were at a conference about using statistics, so perhaps they had better data. Their presentation revealed nothing of the sort. They used the statistics to prove what an epic failure the previous strategy had been. What did they use to prove that their new strategy would be an epic success? A charismatic presentation.

This was a group that believed in themselves. They believed in their intuition. They believed they had a better vision than the last group, a better plan than the last group (in UMC world, it all begins with a good Ministry Action Plan [MAP]), and better systems for implementation than the last group.

So a question I’ve begun asking in leadership rooms: “What if the people who were doing this eight years ago were just as smart and talented and driven as we are?”

And a statement I’ve begun making: “Until our track record improves, I refuse to trust our intuition.” (Another leader tells me I’m giving him a complex. He doesn’t trust anything he thinks anymore. I make no apologies.)

This presents an internal conflict for most leaders: We love our intuition. We believe in ourselves. We believe in our ideas. We believe we know what we’re doing.

So we spend $15 million on a big new strategy that we’re sure will work. Because we’ve read books about it and heard people talk about it at conferences. Because we’ve had long meetings (8 hours!) where we developed exciting mission statements and MAPs. Because we’ve heard ourselves casting that compelling vision, and it sounds pretty good.

When these strategies fail, it should be cause for us to question our intuition. We rarely do. Instead, we assume that the problem was that group’s intuition or talent or drive. With hindsight, we say, “They should have known.” Or, “They didn’t execute properly.”

And then we say to ourselves, “We’ll get it right this time.”

And then we give a new presentation about the exciting thing we’re about to do.

Something besides intuition

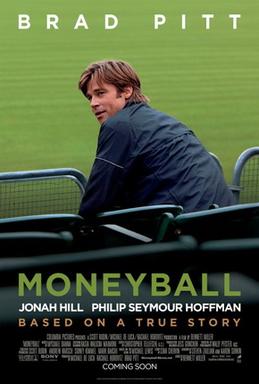

One of my favorite movies in the past decade was Moneyball. It showed its viewers just how silly some of our intuitive reasoning can be.

In Moneyball, we see baseball scouts evaluating players based on how attractive their girlfriends are, how their swings look, and what kind of confidence they project in the locker room. They prefer players who get to first base with a hit and dismiss those who get walked a lot. The based-on-a-true-story plotline is built on this line in the movie: “There is an epidemic failure within the game to understand what is really happening. And this leads people who run Major League Baseball teams to misjudge their players and mismanage their teams […] Baseball thinking is medieval. They are asking all the wrong questions.”

In Moneyball, the answer was to properly identify which results mattered and then to meticulously analyze what was enabling those results. They did not rely on their intuition. They relied on the cold, hard analysis. They did strange things like trading their only first baseman, trading away players everyone thought were stars for players no one had heard of. The person making all the trades didn’t even watch the games.

If my experience at the “nerd camp” conference was any indication, most of us would like to stick with the medieval thinking. We’re reluctant to do hard analysis and then go where it leads us. Why? Because it challenges our conventional wisdom. It limits our options and takes away our own decision-making control. It may not let us do what we want to do.

Most of our decision-making is comfortably intuition-based. Planning is easy –– and rather exhilarating sometimes. Just crafting that beautiful plan makes us feel like we accomplished it.

A brilliant man named Lovett Weems said at that conference: “If you have a proven track record, the path to success is simple:

Plan It –> Implement It –> Celebrate Your Success

“If you don’t have a proven track record, that strategy makes no sense.”[note] My best memory of his exact quote.[/note]

In the next post, I’ll ask about some areas where it might be time to stop trusting our intuition and try a Moneyball strategy instead. Namely, church planting, pastoral transitions, and our process for developing strategy in general.

Until then, how’s your track record? If it’s good, keep on doing what you’re doing. If you’re meeting because things haven’t been going too well, ask yourself, “What if the last group working on this was just as smart, talented, and driven as us?”

To be sure you get that next post, click here to subscribe.