See part I, “Blessing and Delight.” Or see the beginning of this ongoing series on Christ in Culture.

Looking to have a good existential crisis? Let me recommend the book of Ecclesiastes. A quick read may convince you it’s the most hopeless, depressing book in the Bible. Written by someone who needs to get a grip.

Here’s the book’s delightful beginning:

“Meaningless! Meaningless!”

Ecclesiastes 1:2

says the Teacher.

“Utterly meaningless!

Everything is meaningless.”

That opening line uses the Hebrew word hevel five different times. The word translates as “meaningless” here.[note]See only four here? It’s because that Utterly meaningless line uses hevel twice. You might also be able to say “Meaninglessly meaningless” here.)[/note] To give you a general sense of that word hevel, here are all of its uses in another bleak book, the book of Job (the translation of hevel in bold):

- My days have no meaning.[note]Job 7:16[/note]

- Why should I struggle in vain?[note]Job 9:29[/note]

- How can you console me with your nonsense?[note]Job 21:34[/note]

- Why this meaningless talk?[note]Job 27:12[/note]

- Job opens his mouth with empty talk; without knowledge he multiplies words.[note]Job 35:16[/note]

It’s a word that sometimes is used to talk about things being a mere breath or vapor. A word that suggests emptiness. Empty talk. Empty action. Empty life.

In the book of Ecclesiastes, the writer comes back to hevel about every six verses. Think of your downer friend who only speaks up to make sarcastic comments about how GREAT it is that his job is miserable and he missed the fantasy football playoffs because of a Monday night fumble.

Except the writer of Ecclesiastes isn’t just a downer about his life. He sounds like a downer about life. He calls it all a “chasing after the wind.” A few things that he calls hevel:

Wisdom and Knowledge – So you thought maybe he’d just come after frivolous things? Sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll? But instead, the writer comes out––in a book that’s part of the Old Testament’s Wisdom Literature––and says wisdom and knowledge are empty pursuits.[note]See Ecclesiastes 1:16-17[/note] Hey You, pursuing your next degrees and reading philosophy in your free time … it’s all a waste. “With much wisdom comes much sorrow,” he writes, “the more knowledge, the more grief.”[note]Eccl 1:18[/note]

Pleasure, Laughter, Eating and Drinking – “What does pleasure accomplish?”[note]Eccl 2:2[/note] These are all meaningless, too, according to Ecclesiastes.

In my Wesleyan world, which can tend toward asceticism, maybe this one will be a bit easier to accept. Quit with all the indulgence and go do something!

While we might turn up our noses at delicacies, most of us would still say we delight in simple things—reading a good book, taking a walk, a coffee to start the day, time with friends talking and laughing.

Here’s something for you to try. Next time a friend posts a picture of friends on Facebook or Instagram and says something like, “Had a great time catching up with special people last night,” hit the comment button, hit your caps lock, and write MEANINGLESS!

Sounds like what Ecclesiastes is trying to do for us here.

Work and Success – For the people who were okay with pleasure being meaningless, the next one might hit harder. The writer talks about undertaking great projects, making gardens and parks and reservoirs. “Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had toiled to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind.”[note]Eccles 2:11[/note]

We’re in full-on existential crisis here. And it’s part of sacred Scripture. Is this the Word of God for us?

Good or Meaningless?

My last post focused on the goodness of all created things. Sex is good. Food and drink are good. Work is good.

What do we do with a biblical book, then, that calls it all meaningless?

That word for meaninglessness that we keep seeing––hevel––is an interesting word. You saw how it’s used in Ecclesiastes and in Job. In the rest of the Old Testament, most of its uses are references to idols. When God says the Israelites have provoked him to anger with their idols, he literally says, “they have provoked me to anger with their hevels.”[note]Deuteronomy 32:21[/note] It fits. These idols they were worshiping were worthless, empty, meaningless. An idol is a nothing.[note]See 1 Corinthians 8:4[/note]

And look at what God says happens to these idol worshipers.

This is what the LORD says:

“What fault did your ancestors find in me,

Jeremiah 2:5

that they strayed so far from me?

They followed hevels

and became hevel themselves.”

The NIV translates that as “They followed worthless idols and became worthless themselves.”

Rethinking Idolatry

We need to reconsider two of the common ways we think about the idolatry in the Old Testament.

First, we tend to think of idolatry mainly in terms of provoking God’s anger. We think of the outward damage idols caused between the people and God. That’s a real thing. We just saw it above, where God said, “They have provoked me to anger.”

But in my experience, we rarely talk about the inward damage that’s done. What happens when people worship these worthless, meaningless, empty things? God says they become worthless, meaningless, empty themselves.

Existential crisis.

Think of the blank stare of someone under the influence of certain drugs. Or the empty existence of people that Wall-E depicts. They followed worthless things and became worthless themselves…

What we pursue starts to define who we are.

Second, we tend to relate idolatry to primitive people who were silly enough to believe that something carved from wood or stone could actually be a god. We wouldn’t fall for this.

I wonder if the book of Ecclesiastes unmasks what idolatry is really about. Not just for us, but even back then for those primitive people. When you think about idols, don’t just think about carved wood and stone. Think about what’s behind those empty things. Think about what Ecclesiastes calls empty: wisdom and knowledge, pleasure and laughter and eating and drinking, work and success.

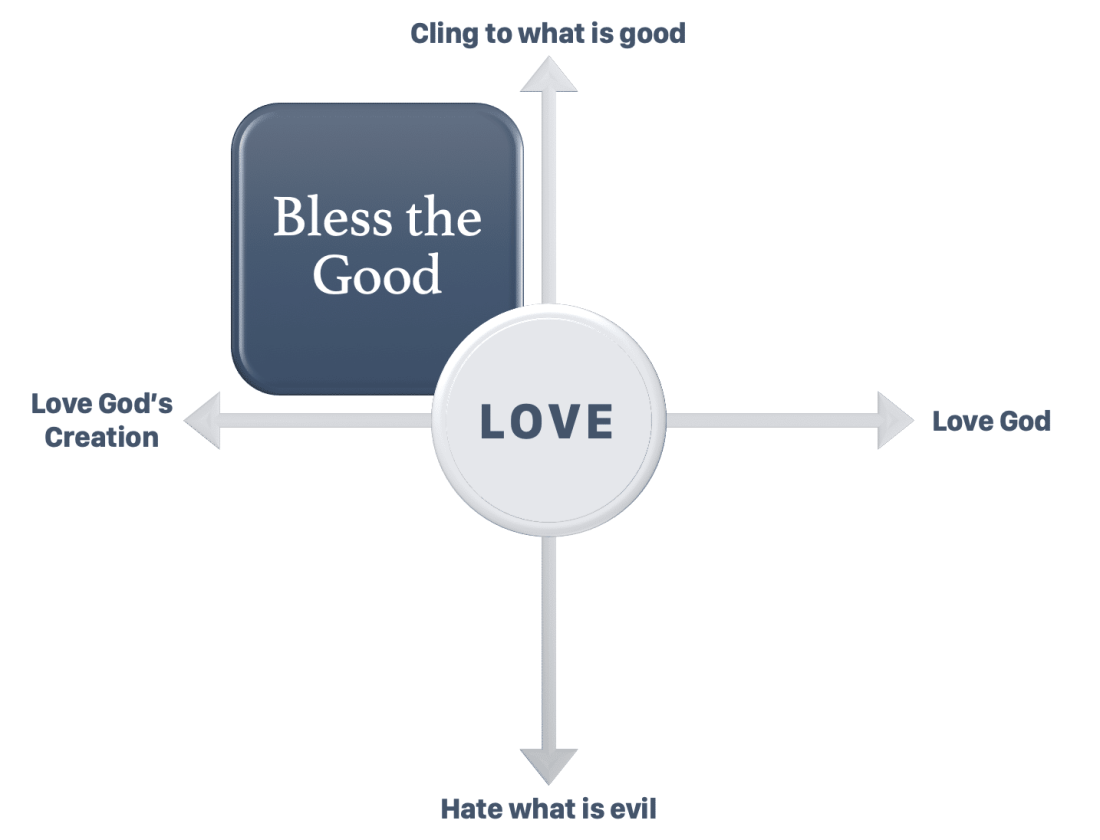

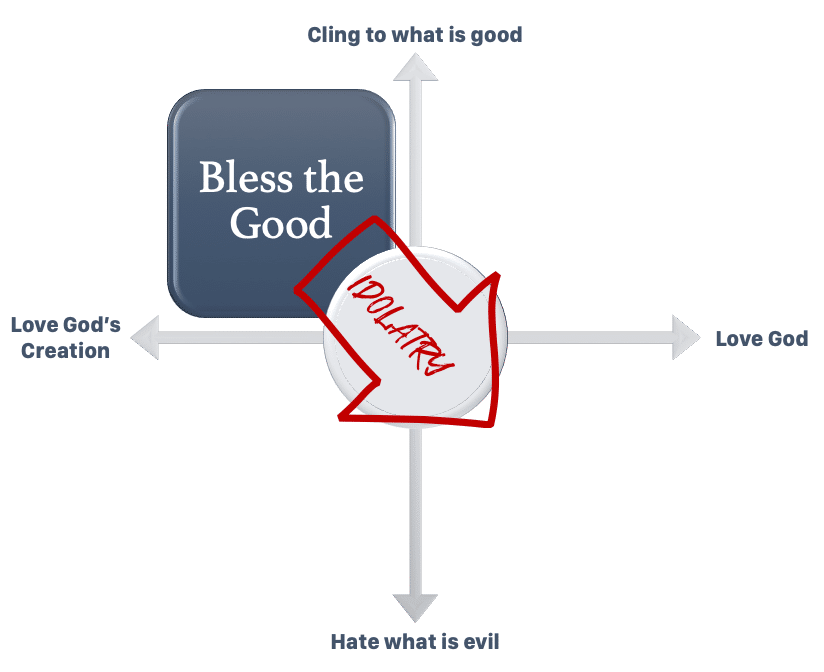

I want to suggest to you that idolatry is not usually about bad things. Idolatry is about good things that we have turned into gods. We are moving things from the category of God’s good creation, which we bless, to treating them as gods.

God and gods

Who is God? God is the one who gives our lives meaning. God is the one we trust and rely on to see us through our hardest times. God is our ultimate desire, the one we pursue because life would be empty without him. God is the one who tells us what is good (and we cling to it) and what is evil (and we hate it). God is our goal, our end, our reason for being.

Who are our gods?

They’re whatever we go to for our meaning and purpose in life. Ecclesiastes: “When I surveyed all that my hands had done […] everything was meaningless.”

They’re whatever we turn to in our hardest times. Ecclesiastes: “I tried cheering myself with wine.”

They’re whatever desires we pursue because we believe life would be empty without them. Ecclesiastes: “I denied myself nothing my eyes desired.”

They’re the ones we allow to tell us what is good and what is evil.

They’re our goal, our end, our reason for being.

The story of humanity’s idolatry is a story of people turning to God’s good gifts in the times that we should be turning to God himself. When we do, those good gifts turn out to be empty. Not because they’re entirely worthless, but because they’re unable to take the place of God.

Food and drink

What do you do when you receive bad news? When you’ve had a hard day? When you’re overwhelmed or scared?

In the book of Esther, a king issues an edict to have all the Jewish people in his kingdom destroyed. When the Jews learn about the edict, they respond with mourning, fasting, weeping and wailing.

In the book of 2 Chronicles, the king of Judah learns that “a vast army” is coming to attack the people. Rather than calling his army to take up arms, he resolves to inquire of the Lord and proclaims a fast for all Judah.

When some of the worst news comes, they respond with fasting. What a difference from some of our most typical responses! For many of us, with a hard day or bad news, we take the Bridget Jones path. We choose ice cream or vodka. Or maybe both. (Or whatever our food and drink choices are in these times.)

In their hardest times, Israel stops eating and drinking. In our hardest times, we often over-eat and over-drink. Why? We go to these for some sort of relief, some way of numbing ourselves to the hardship of life. Rather than turning to God in these times, we turn to food and drink. And at this moment, these stop being good gifts of God and become something they were never intended to be––our go-to in hard times. That’s God’s role. We could say that the good things have become gods.

Food and drink are good. The people of God gather for huge feasts throughout the Bible, complete with alcoholic beverages. But when people turn to them to fill a deeper longing that these were never meant to fill, it’s gluttony, a sign of idolatry.

Through the practice of fasting, I’ve learned about some of the unhealthy ways I’ve used food. I find myself up, walking around, looking for food, not because I’m hungry, but because I’m bored. Or frustrated. Or tired. I want a drink at night specifically because it has been a hard day.

The food and drink don’t solve the problems. They just numb us to feeling them for a moment. Follow these empty solutions for long, and we become empty ourselves. If you find yourself turning to food or drink to cover over other frustrations or anxieties, there’s a good chance it’s idolatry.

Sex

Sex is good. It’s a beautiful, mysterious creation of God. It should draw us closer, not just to each other, but to God.

When does sex become idolatry? When sexual identity is what gives our lives meaning. When we treat sexual activity as a necessary part of life, without which our lives would be empty. When we treat others’ bodies as cheap pleasure-delivery devices rather than as gifts for intimacy and procreation in marriage. Easy access to pornography (now not just in X-rated movies, but in “must-watch” TV series) is giving us easier ways both to hide and to justify this idolatry. But the ease of justification will leave us no less empty for it, and the ease of hiding it will put us in greater danger.

Sex has become not just a personal idol in our time, but a political idol. Other than partisan politics itself, the clearest dividing line we have between allies and enemies is often drawn according to views on human sexuality. For both sides, beliefs about same-sex marriage have become an easy shibboleth for friend or foe. Sexual politics have caused some religious people and groups to shun anyone who doesn’t hold to their standard or represent their position. This has been especially hard for celibate gay Christians. As one friend said to me, “Everyone has a problem with one of those words.”

Being a celibate gay Christian is like being an early preacher of a Christ who was crucified and rose from the dead. You represent something that seems mad, irrational, foolish to our culture of desire and sex. We are fools for Christ’s sake, weak and pressed at every side.

— David Bennett (@DavidACBennett) November 30, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

One of the deep kinds of vulnerability gay (celibate) people experience is called “apologetic objectification”: we are used to justify an ethic or virtue-signal progressive or conservative causes but not loved or known as sons of God. This is a problem I don’t know how to prevent

— David Bennett (@DavidACBennett) November 30, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Sex is good. We don’t need to affirm its goodness in all instances to believe that it’s good. The demand for that blanket affirmation turns this good into a god, giving it a place God never intended in our world and in our lives.

Several others

I won’t go into detail on the many other ways goods things can become gods. A few brief words.

Work – It’s good. It’s meaningful. God puts Adam and Eve in a garden to cultivate it. Work becomes god when it defines us, when the meaning and value of our lives is defined by our accomplishments. When work becomes god, we trust in ourselves and the work of our hands rather than God. When work becomes god, we neglect other important relationships (to God and others) so that we can get more done. Though it may sound strange, this can be a manifestation of the vice of sloth––neglecting the hard work of love. You can be a workaholic sloth. It may also be about vainglory––the excessive need to be recognized, to receive others’ praise and applause. You’re likely under-recognized and under-appreciated (most people are), and you should receive some recognition for what you do. But when it becomes the thing you’re pursuing, it has become a god.

Money & Possessions – They’re gifts from God that can be used to glorify God. In the last article, I said that money is not the root of all evil. That idea comes from misquoting the Bible. Here’s the direct, extended biblical quote:

For we brought nothing into the world, and we can take nothing out of it. But if we have food and clothing, we will be content with that. Those who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil. Some people, eager for money, have wandered from the faith and pierced themselves with many griefs.

1 Timothy 6:7-10

If we find ourselves constantly agonizing over money, we may have given money and possessions a god-like place in our lives. If we find ourselves consistently discontent because we don’t have enough –– either not enough things, or not enough money to pay for our expenses (beyond simple basics) –– it may be the vice of greed. This is nothing new. Jesus warned, “You cannot serve both God and money.”[note]Matthew 6:24 and Luke 16:13[/note]

Politics – Politics are good. At root, the word is about providing structure and order for a particular body of people. But partisan politics has become one of the great idols of our time. Many of us have allowed partisan political parties to define good and evil for us, both in terms of issues and people. In the U. S., neither the Democratic nor the Republican party––neither Trump supporters nor never-Trumpers––look like the kingdom of God. We give these political parties (and their associated news channels, websites, and radio shows) a god-like status when we walk in lock-step with them in defining good and evil.

Even more, partisan politics are breeding hatred across our country. A claim I’ve made earlier: people are created in the image of God. They’re loved by God. All of them. Even deplorable sinners. (Jesus did not come to call the righteous, but sinners.) Even our enemies. Even our political enemies. Even Donald Trump. Even Hillary Clinton. When partisan politics turns people into objects of our scorn and wrath, it has likely become an idol.

Speaking Truth

We began with the book of Ecclesiastes. “Meaningless! Meaningless! Everything is meaningless!”

Is the book just a big existential crisis? It is at least that. For anyone who seeks meaning in life through any of these good things––work, pleasure, wisdom, etc.––the promised end result is emptiness. All of these, as final pursuits, are empty. They will not satisfy.

More than existential crisis, I think Ecclesiastes is a book on idolatry. Pursue these things as if they were your god, and your life will be meaningless. But it doesn’t conclude by calling life meaningless. In fact, it finds a clear purpose for life. Here’s how the book ends:

Now all has been heard;

Eccles 12:13-14

here is the conclusion of the matter:

Fear God and keep his commandments,

for this is the duty of all mankind.

For God will bring every deed into judgment,

including every hidden thing,

whether it is good or evil.

Life finds its deep meaning in loving, serving, and living in union with God. When anyone takes God’s good gifts and turns them into gods, they lose the meaning of life.

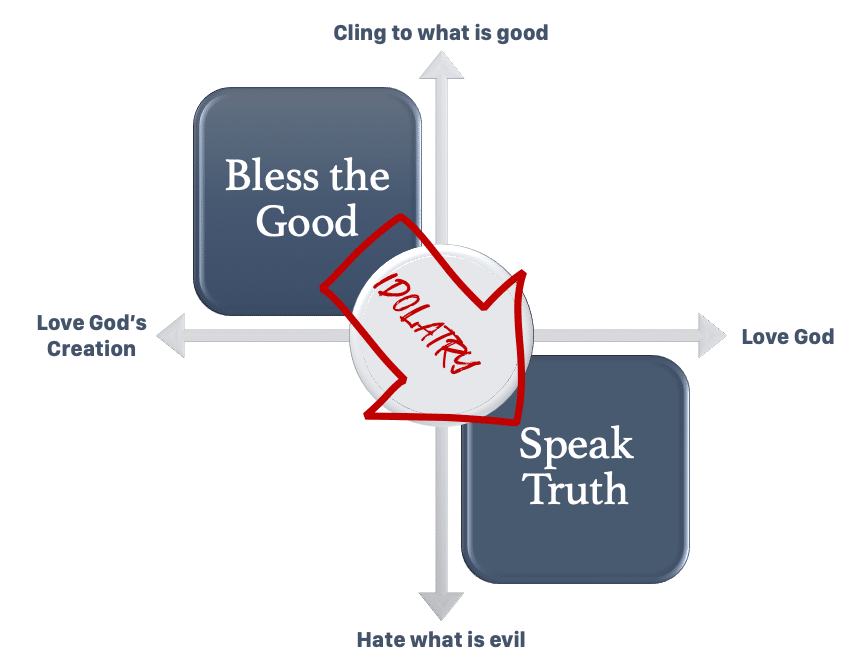

How should the Christian and the Church respond in times when people serve false gods? I believe our best approach is to do as the writer of Ecclesiastes did. I’m calling it “Speak Truth.” This involves two things:

- Unmasking the idols of our world for what they are. How can we show people––gently, if possible––the utter emptiness of the things they’re turning to in place of God?

- Pointing people to the true God. He is the one who redeems us from the empty way of life handed down from generation to generation.[note]See 1 Peter 1:18[/note]

Be slow to see this as a prophetic word delivered from people who call themselves Christians to people who do not. We should try to unmask the idols of our secular world and point it to God (again, gently where possible). But much of the truth we speak will be to others who already call themselves Christians. In fact, the first and most consistent truth we seek should be for ourselves. Most of us carry on with low-grade idolatries, unaware of just how much we are influenced by them. We would be better to recognize them for what they are, let the good things be merely goods, and let God be God.

See part I, “Blessing and Delight.” Or see the beginning of this ongoing series on Christ in Culture.