[When you’re done, see my newest post: “The Lectionary and the UMC: The subjects of our verbs.”]

Throughout the history of God’s people, religious renewals have followed a similar pattern. You’ll be unsurprised to know these renewals didn’t begin with a change to policy or structure or a 55-45 vote. Here’s how William J. Abraham describes the Lutheran and Wesleyan renewals, among others:

“They took to immersion in the scriptures, to study of the tradition, to intentional participation in the sacramental life of the church, to prayer, and to extended conversation with their friends.” [note]In his brilliant Waking from Doctrinal Amnesia, p. 91[/note]

As the United Methodist Church faces a time of crisis, I’m convinced that renewal will not come through a vote at our General Conference or the next great policy proposal (not that these are entirely insignificant). It will come the way renewal comes, when we immerse ourselves in the scriptures and prayer and the church’s tradition and sacraments––and when we have extended conversation with each other concerning these practices and shaped by them.

To be sure, we can’t undertake these practices for the sake of proving ourselves correct. We do it to seek a word from God. Or perhaps better, to stop making ourselves the subjects of all our verbs and instead to say, “Speak, Lord, for your servants are listening.”

Whether you are United Methodist or not, might we ask how God speaks to us––not just as individuals, but as communities of people, even denominations––through his scriptures? What if we immersed ourselves in the scriptures according to our own lectionary? Does God have a word we can hear together here?

Avoiding Uzzah

The Old Testament lectionary passage for this week (2 Samuel 6:1-5, 12b-19) is as remarkable for what it leaves out as for what it contains. The passage narrates the arrival of the ark of God in Jerusalem. It leaves out Uzzah’s sudden death.

Verses 6-7, missing from our prescribed lectionary reading:

“When they came to the threshing floor of Nakon, Uzzah reached out and took hold of the ark of God, because the oxen stumbled. Yahweh’s anger burned against Uzzah because of his irreverent act; therefore God struck him down, and he died there beside the ark of God.”

The lectionary frequently leaves out portions of passages. Sometimes that’s for the sake of brevity, other times for the sake of focus on one particular aspect of the passage. In this case, though, I suspect it’s to avoid having to deal with what happened to Uzzah. This makes sense to me. I’d probably prefer to avoid it. But an honest immersion in the scriptures doesn’t let us off that easily.

Why are we uncomfortable with the Uzzah passage? It seems like the wrong answer to a common question: “Would a loving God really do that?” How could a loving and compassionate God strike someone down? And for this?

Richard Dawkins loves texts like this. He uses them as basis for a central claim in The God Delusion: “The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak…” [note]p. 51. That sentence keeps going for quite a while longer.[/note] Uzzah tries to steady the ark on the cart and God strikes him dead. Uzzah’s (ultimate) punishment does not seem to fit his (very minor) crime.

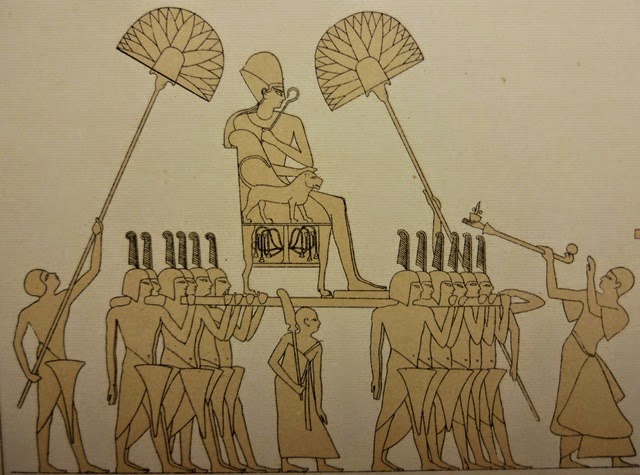

Uzzah’s demise traces back to Numbers 4:15: “After Aaron and his sons have finished covering the holy furnishings and all the holy articles, and when the camp is ready to move, only then are the Kohathites to come and do the carrying. But they must not touch the holy things or they will die. The Kohathites are to carry those things that are in the tent of meeting.”

The ark of God––the throne of God on earth among the Israelites––was intended to be carried like this.

Does that look familiar?

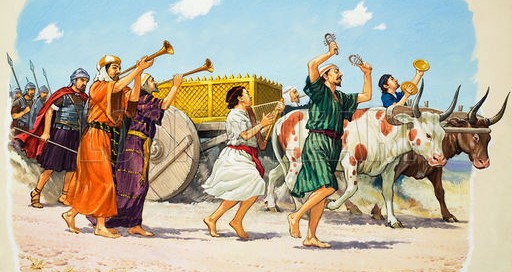

Looks kind of like this.

A royal procession for a King.

Instead, the Israelites chose to move the ark of Yahweh as if it were luggage, loaded onto an oxcart.

Uzzah’s decision to reach out and touch the ark, disregarding God’s command and God’s holiness, was far from the first act of irreverence on the part of the Israelites. But it was the action that resulted in Yahweh’s wrath finally breaking out.

When we ask whether a loving and compassionate God would strike Uzzah dead, our hearts want to say no. But God did strike Uzzah dead, and while our lectionary can avoid it, we cannot.

Essential but not Sufficient

God’s compassion is an essential part of understanding the nature of God. But God’s compassion alone is not sufficient for understanding God. We make a great mistake when we confuse essential for sufficient.

Along with recognizing God’s compassion, we must recognize what the Israelites here ignored: God’s holiness. They had been told to fear Yahweh, to walk in obedience to him and observe his commands and decrees. This, too, was an essential part of their understanding and knowing God. Uzzah’s death was a result of their lack of fear and obedience.

When we avoid Uzzah to focus on a God of compassion, we don’t get a better God, we get a false god––one of our own making.

We could also do the opposite––to fixate on the God who strikes Uzzah dead. This is how Richard Dawkins would prefer it. But that overlooks the God who mercifully returns to be Israel’s God––visible in the ark’s procession to Jerusalem––even after their repeated rejections and rebellions. If we did this, we would likewise be worshiping a god of our own making, one who desires sacrifice, not mercy.

The Lectionary and the UMC

There are two common watchwords right now in the UMC: compassion and orthodoxy. Both are essential to the Christian faith. Neither is sufficient.

Compassion tells us to listen to those on the margins, the minorities, the least of these. Orthodoxy tells us to listen to those who’ve gone before us. Who should we listen to? Both!

Compassion tells us we should give special attention to care for the marginalized and oppressed, whatever the cost. Orthodoxy tells us we should give special attention to reverent obedience to God’s word and the church’s historic teaching, whatever the cost. Which should we tend to? Both!

Compassion tells us we should be wary of injustice. Orthodoxy tells us we should be wary of heresy. Which should we be wary of? Both!

Our problems come when we take either of these not just as essential, but as a sufficient rule for our faith and life, and thereby nullify the other.

If I find myself regularly citing those on the margins, I may need to spend extra time listening to those who’ve gone before us (and not just those who say what I want to hear). If I find myself regularly citing those who’ve gone before us, I may need to spend extra time listening to those on the margins (and not just those who say what I want to hear).

Our church cannot avoid Uzzah. God is a holy God. His eyes are too pure to look on evil; he cannot tolerate wrongdoing.[note]From Hab 1:13[/note] Neither can our church fixate on Uzzah. His death shows us only part of God’s nature. Yahweh is still a compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love.[note]Found throughout the OT. See, e.g. Ps 103:8; Jonah 4:2[/note]

Like it? Or just want to discuss it more? I’d be honored if you’d share it –– use the social media links at left. Or send me an email for follow-up discussion. Or if you haven’t already, click here to subscribe for more. Thank you!

[When you’re done, see my newest post: “The Lectionary and the UMC: The subjects of our verbs.”]