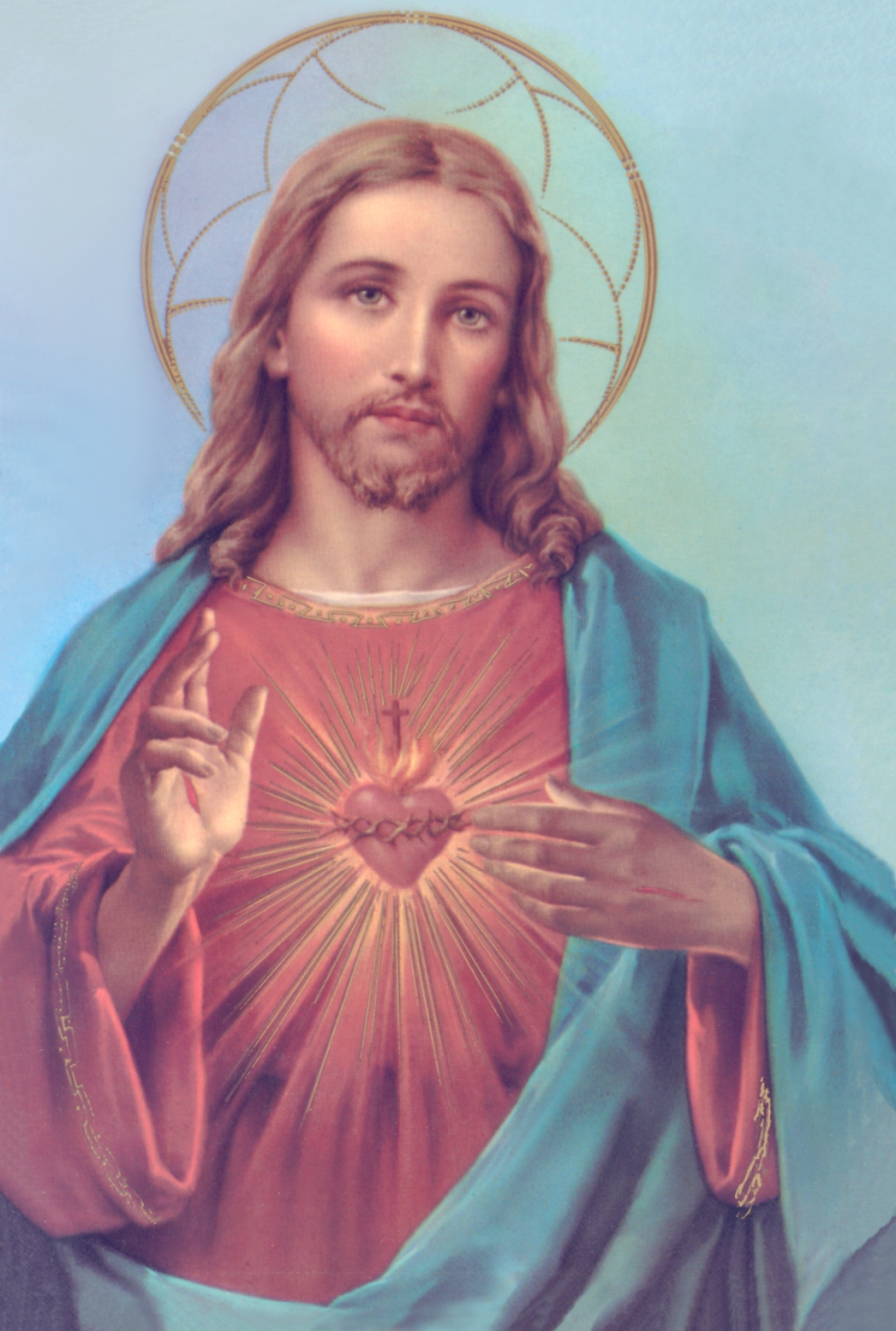

Let’s get this straight—despite Megyn Kelly’s recent protestations, the ethnicity of the historical Jesus is pretty well settled. He was a Galilean Jewish man, almost surely with darker and more olive-toned skin than a typical white man. He didn’t have blue eyes. He didn’t have a golden halo hovering above his head or perfectly blow-dried hair. He probably didn’t even have long hair.

Why we need to acknowledge that Jesus was a Galilean Jew

First, it’s a shame that we’re having to say this at all. We have to say it because, as Megyn Kelly has shown us, some people really think the historical Jesus was a white man.

It affects how we read the Bible when we imagine this sort of supernatural figure walking among the masses. He seems not quite human, more floating than walking. We picture this type of mystical figure and have a hard time understanding how the world didn’t recognize him. (Here I’m not referring to his whiteness—which is nothing supernatural—but the total aura.)

We see these images of Jesus, clearly out-of-place in a world full of regular-looking (sometimes even Jewish-looking) shepherds and fishermen, and his humanity seems almost an illusion. It’s hard to imagine that he could have actually gotten his feet dirty, smelled bad, or stubbed his toe. That all makes it hard to imagine he understood or had to deal with our actual human plight. All of that, though, dances on the edge of an ancient heresy called Docetism, which held that Jesus only appeared to be human.

One of the great marvels of the incarnation is that the Son of God became a real, regular-looking human being. He came into a particular culture as one of the people of that culture. We lose the significance of that when we portray Jesus as a conspicuous foreigner among a bunch of first-century peasants.

When we forget that Jesus was of Jewish descent, we also miss an enormous theme that runs throughout the Bible: God chose Abraham and then the people of Israel to bring salvation to the world. Salvation is from the Jews! Forget that Jesus was Jewish and you’ll misunderstand a lot of the Bible––both Old and New Testaments.

When Jesus isn’t a Galilean Jew

The historical Jesus was a Galilean Jew, and we must recognize that for all the reasons above. But I think there are theological reasons to accept some other depictions.

The painting at right is of Chinese Jesus. Why would anyone paint Jesus and his followers as if they were Chinese? We all know this isn’t historically accurate.

I think they would do it because Chinese people will understand the incarnation differently when they see a Chinese Jesus. Although Jesus surely didn’t speak Chinese and never set foot in modern China, I think the painting at right might help a Chinese person understand some of the deep theological realities of the incarnation better than a painting of a Galilean Jew.

I’ll make the same statement as above, but now with a slightly different intention. One of the great marvels of the incarnation is that the Son of God became a real, regular-looking human being. He came into our time to experience what we experience, to share in our limitations and hardships. “We do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet he did not sin” (Hebrews 4:15).

This is where we run into something called the scandal of particularity. Jesus didn’t experience everything. He didn’t experience life in medieval Europe or 21st century Africa. He didn’t experience life as a woman or as an elderly man. We might even ask if he was really tempted in every way. He was unable to experience all of these things precisely because he was human. To be human is to be limited by time and space.

Jesus’ incarnation required him to come into a particular time and place with a particular ethnicity and race. The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among a group of first-century Jews. While the gospel of John doesn’t mean less than that, I think it intends to mean more than that. When we read, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14), I think we’re intended to read that “us” as even ourselves. I think we’re intended to see all the particularities of Jesus’ thirty-something years of life on earth and see broader implications in them––that he is truly able to empathize with all of our weaknesses and situations, even those he didn’t directly experience.

I suspect that many people in China would feel that point more deeply if they saw a picture of Chinese Jesus. Could they comprehend it while looking at a Galilean Jewish Jesus? Surely so. But I think they would feel it differently. What language would Jesus speak to a woman from Beijing? I expect it would be Mandarin Chinese––probably with a Beijing dialect. That’s easier to expect when you see a Chinese Jesus.

Let me stop and acknowledge here that our world is quickly globalizing. A woman in Beijing may meet someone who appears Jewish or African and then find out that person speaks perfect Mandarin, with a Beijing dialect even. People don’t have to look like us to be like us. While that’s true, I don’t think it’s enough for me to tell a Chinese friend to get rid his Chinese Jesus picture.

So I’m okay with Chinese Jesus. And also Indian Jesus and Hispanic Jesus and Ethiopian Jesus –– all for the same reasons. Can we continue to remember that the historical Jesus was a Galilean Jew and yet continue using these other images, as well? I hope so.

Why I’m (cautiously) okay with white Jesus

For all the same reasons I just gave, I’m okay with white* Jesus depictions. Just as I think an Ethiopian might see Jesus a bit differently––and more truly––if she sees an Ethiopian Jesus, I think a white person might see Jesus differently if he sees a white Jesus.

I’m more cautious of white Jesus than any other depictions, though. I’m cautious because people like Megyn Kelly actually believe that Jesus was white. They’ve seen so many white Jesuses that they have lost any sense of his true historical ethnicity. I’m cautious because we don’t need a white Jesus to suggest any more white privilege to our world. I’m cautious because of how prevalent white Jesus seems to be in the Western world––so much so that it might be hard for Westerners of other ethnicities to picture a Jesus that looks more like them.

When I was in seminary, a guest speaker came to one of my classes and celebrated all the great things about his ethnic heritage. He talked about the ways that they were including specific parts of that heritage in their worship, and it was beautiful. But then he looked at all of us (nearly all white) and said, “You need to remove everything that reflects white culture from your churches. White culture has done too much evil.” He went on to tell us that we had no ethnic heritage, and when someone asked what cultural patterns we should adopt, he told us to pick any other than our own.

I suspect that this man had been deeply hurt by what he called “white culture.” I’m sure many of his family and ancestors had as well. I regret that. Nevertheless, I don’t believe those past hurts are cause for telling anyone that they have no culture and should go and adopt someone else’s. For that reason, just as I’ll support a Chinese Jesus, I think there is still a place for a white Jesus. I don’t think we should rid ourselves of those depictions, though I think it’s time our depictions got a bit more diverse. Let’s keep white Jesus, but let’s be sure to add Jesuses of many other ethnicities to the mix. Most of all, let’s be sure Galilean Jewish Jesus has some prominent place in our vision.

———–

Excursus: A Female Jesus?

This discussion leads us to another important question. If we can depict Jesus as Hispanic or Indian, African or Chinese, can we depict Jesus as a woman?

Let me first say that I believe we have a Savior who empathizes with women just as well as with men. He understands their thoughts and experiences no less. And by no means does God favor or honor one gender over another.

But I wouldn’t depict Jesus as a female. Augustine says Christ “was not ashamed of the male nature, for He took it upon Himself; or of the female, for He was born of a woman.” Thomas Oden offers this as a hypothesis: “If the mother of the Savior must necessarily be female, the Savior must be male, if both sexes are to be rightly and equitably involved in the salvation event.”** I think there’s something important to keeping Jesus as a male, the Son of God, born of a woman.

I suspect my thoughts here represent a minority view. I’ve gotten myself into issues of race, gender, ethnicity, and historical accuracy. I’d be interested in your thoughts in the comments.

* I wade into all sorts of murky waters by using the word “white” here. I use it the way that Wikipedia defines the term “white people” to refer to a set of ethnic groups characterized by lighter complexions and with origins in Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

** All of this from Thomas Oden’s Classic Christianity, p. 505.