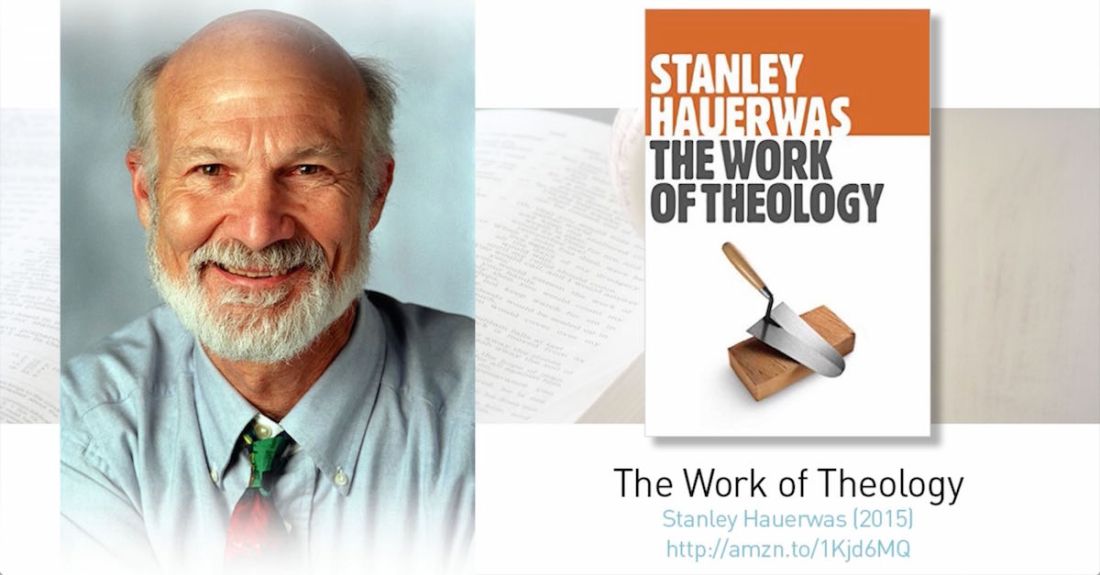

I recently had the honor to interview Stanley Hauerwas about his newest book, The Work of Theology.

One reviewer has called Dr. Hauerwas, “probably the most creative, provocative, and exasperating theologian in the English-speaking world.”[1. from The Times Literary Supplement‘s review of his Blackwell Companion to Christian Ethics] This book continues to show off his creativity and shows how some of it has developed. It also serves as a response to those Hauerwas has provoked and a defense against those he has exasperated. I thoroughly enjoyed the book and enjoyed the opportunity to talk with him about it even more.

Our interview covers his responses to critics, why he gives so much emphasis to the church, and some advice for young pastors and their congregations. You can listen (right-click here to download), watch, or read the transcript below. [1. My deepest gratitude to Jason Huber for producing this. His studio, graphics, and detail work made it all possible.]

Interview transcript

Teddy Ray: Stanley Hauerwas was named the “best theologian in America” by Time magazine in 2001. Despite that, he’s also been accused of not caring about the poor, not caring about human rights, and not actually doing “theological” work. He thinks retirement is a bad idea, and he’s having some more time to reflect on that now that he’s retired. His newest book is called The Work of Theology, and I’m honored to have a chance to talk with him about it.

Dr. Hauerwas, thanks so much for your time this morning.

Stanley Hauerwas: I’m pleased to be here.

TR: I’m going to jump to the end of your book because it seems like something you say on almost the last page is the basis for a lot of the book. You say about doing theological work, “You finally cannot stop because what you have said makes it necessary to respond to the problems that are created by what you have said.” Is that what a lot of this book is?

SH: Yes. I think that’s a good… I hadn’t really thought about that as being a kind of summary of the book, but I think you’re quite right. That’s what the book’s about.

TR: In particular, I was struck by the way you kept coming back and saying, “Here’s what people have accused me of, and let me set the record straight. Or let me say a little more to try to help them understand what I’m really doing.” How do you, as such a public theologian, handle all of the different criticisms? You’re a big target, obviously. How do you handle those when people take you the wrong way, or when people say things that you feel like aren’t fair or aren’t true about you?

SH: Well, you’re never happy about being misunderstood, but you have to take responsibility oftentimes for being misunderstood, because you think you haven’t put it as well as it could be put. So even misunderstandings are a gift that make you think again about what you need to say, given that you’ve created this misunderstanding. Often, one of the problems that you confront when you’re trying to change the questions, not just the answers, is that people insist on interpreting you by saying that you must be meaning what they would mean if they said the kinds of things I said. And I’m not in the same position they are in. So it really is a mostly generational problem, just to the extent what I represent, I think, is a different set of considerations than have been characteristic of particularly American Protestant theology in the last fifty years.

TR: That’s interesting. So when you say you’re in a different situation, you’re really referring to people younger and people coming from different traditions—Nicholas Healy coming out of the Catholic Church—addressing different things than you’re trying to address.

SH: That’s some of it, though I think he is a very good critic, and while I’m not particularly sympathetic with every kind of argument he makes against me, I take him very seriously.

TR: Let me go to one of the quotes—I think I counted this at least 10 times in your book—and it seems to be one that people have especially come back to you about over and over. You say, “The first task of the church is not to make the world more just but to make the world the world.” Could you say more about that? Pastors and churches are told a lot of different things about their first task, and I’d love for you to say why that’s how you’re naming it.

SH: Well, of course, it draws on the Gospel of John. You don’t know that there is something out there called the world unless there is an alternative to that, and that’s called church. So the fact that there is a gathered body of people around the world that are interconnected through the Holy Spirit creates an alternative that is named world.

Now world is God’s good creation, that has taken the time of God’s grace not to be church. That doesn’t mean everything about the world is wrong, but it does mean that the world simply lacks the possibilities that the church has been given by God’s good grace. And that’s an eschatological set of judgments about why it is that God has called out a people from the world to be for the world, so that the world might know what it means to worship God.

TR: That’s great. I think you even said somewhere else that some of your critics have claimed your stress on the church tempts you and those influenced by you to ignore the world. From what I hear you saying and everything I’ve read, it seems that they’re confusing ignoring with being separate from the world. Is that a fair distinction?

SH: I certainly… Everything you do as church is to be a witness for the world. So you have to take the world very seriously, indeed.

TR: I think what I love most about reading your work is that you help me love the church more—as a pastor and as a worshiper. And it’s not just the church that could or should exist. It’s the church that actually exists.

SH: Well, I certainly hope so. People accuse me of having an idealistic view of the church, and I say, “How can that be? I come out of Methodism!” You can hardly have an idealistic view of the church. I go to a wonderful church, and I’m very happy that we’re there, but I don’t assume that we’re without blemish. We’ve got all kinds of problems.

TR: And by no means do you avoid those.

SH: No. I try not to.

TR: So for me, at least, what you’ve done for me isn’t so much to discourage me. It compels me to keep urging the church to be the church. And that’s what I appreciate. There’s this high, lofty thing, but it’s also to say, “This is who we should actually be, and let’s not give up on the church when we’re not that. Let’s keep striving to be that.”

SH: I keep saying, “It’s a miracle that the church exists.” I mean, that it just exists. What an extraordinary thing, in the world in which we find ourselves, that there exists a body of people set aside to worship God! I mean, that’s a miracle!

TR: That is very true. And I think with that, of everything in your book, the piece I loved most––and maybe it was because it spoke to me directly as a pastor––was chapter six on theology and the ministry. It seems like that’s where how we live as the church and how pastors pastor the church really come out. You emphasize the need for pastors and priests to be theologically astute, but you also acknowledge several times all the different demands of ministry and all the different directions we can be sent. A lot of the people I’m talking to are young preparing pastors and young pastors. What do you recommend for both them and for their congregations? How do we create that atmosphere for them to be the kind of ministers we need.

SH: I think it’s very important for people in the ministry to train their congregations on why, as ministers, they need to have time set aside to pray and to read. I know that sounds odd, because one says, “Well, they probably are doing that all the time.” No, I just think you need time set aside for study, and study is a form of prayer. And the congregation needs to value that in the minister as something that is crucial if they are not going to burn out.

TR: What do you recommend we do less of, then? For pastors to say, “I don’t have the time to do these things,” or “These shouldn’t be priority things so that we can actually prioritize prayer, study, and reading.”

SH: You have to visit the sick. You have to take the Eucharist to the sick. You have to care for the broken. No one knows, other than the minister, how many marriages are out there just hanging by the thread. And you can’t ignore that. It doesn’t mean that you’ve got to fix it. You’ve got to help people get places that can help them get it fixed.

I think people in the ministry have spent too much time being nice, in the sense they have to make sure they’re interacting all the time, and showing that they’re good people, and so on. And I think that takes a real toll after a number of years. I mean, who wants to go through life always being nice? And so I think that to claim that to be ordained sets you aside to have very particular commitments that require study and prayer is very important. I think the amount of time spent on preparing sermons is important.

TR: Yeah, you really emphasize that. You said, “One of the most fruitful genres for theology remains the sermon.” I love that you keep emphasizing the importance of your works that are sermons, and your Matthew commentary, that people don’t seem to be paying as much attention to as some other work, and you’re pointing to those as primary theological work.

SH: Right. No, I don’t think the Matthew commentary is read very much. I think it’s read by people that are ministers, which I am very pleased about.

TR: So when you say, “not read very much,” it’s not read by laity?

SH: It’s not read by other theologians.

TR: Oh, okay! That makes sense. They think there’s more serious work to be done in the theological books. I had somebody once tell me that if I really wanted to understand Augustine’s theology, I needed to read his sermons.

SH: That’s true! His sermons are terrific.

TR: So let me ask along those lines… Jaroslav Pelikan describes this movement in history, where most of the great early theologians were bishops, then there was a shift, and they were monks, and then after the Reformation, a shift to academics. If you accept his premise in the first place, do you think we’re poised for another shift?

SH: I think there’s a good possibility that that could occur. Obviously, the American university is increasingly secular. It has… What were once, quote, religious schools, have no place for theologians in the undergraduate curriculum. They might have a seminary, and they can exist there. But how long seminaries will be valued by secular universities is gonna be a real question. So my hunch is that theologians will increasingly come from out of the parish. And some of them may be ordained, some of them may not. But it’s gonna be a big change.

TR: Is that one that you would say you celebrate, or just one that you would say, “It is what it is.”

SH: It is what it is.

TR: There are so many other things I’d love to talk to you about. Let me ask just one last question, though. You said, “The theologian always begins in the middle and the theologian’s work is never finished.” Is there any work you’ve especially wanted to get to and it just seems you never get around to it, never get the time for it?

SH: It always seems like whatever you’ve done is only to scratch the surface. And you keep wanting to go back and say more about the virtues. You keep wanting to go back and say more about language about God, and why it’s so fragile. You keep wanting to go back and revisit questions about how the church can become a more disciplined community, and so on and so on. So it’s never over, and that’s great! I mean, just think about how boring it would be, if it was.

TR: That’s where I love how you present retirement. Now you just have more time to keep on working on those things. I don’t understand the concept of retiring and just quitting on things like that, either.

SH: I’m very fortunate to have a task that’s never over!

TR: The job is never done. Nice job security.

Well, Dr. Hauerwas, our time’s up. Thanks again for being so generous with your time this morning.

SH: Well, I was pleased to do it, and I wish you well.

Dr. Hauerwas’s most recent book is The Work of Theology. We’ve just barely skimmed the surface of so many topics he addresses there. For more, pick up his book. You can find it here.

I’ll have more interviews like this forthcoming. To see them all, sign up to receive my blog updates, along with other exclusive subscriber content.

————–